IBM says it has come up with a method to fuse a metal contact point to a carbon nanotube transistor, overcoming a barrier to nanotube CPUs.

Apple, Microsoft, IBM: 7 Big Analytics Buys You Need to Know

Apple, Microsoft, IBM: 7 Big Analytics Buys You Need To Know (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

In its second year of investing in "post-silicon" chips, IBM finds itself at the crossroads where computer science meets materials science.

Now, Big Blue is claiming it can not only build carbon nanotube transistors, a claim widely acknowledged as feasible, but it can also connect the nanotubes to other processor components and circuitry, a claim no one else has made so far.

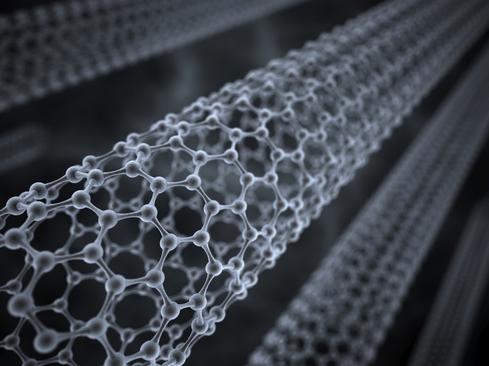

Nanotubes are a rolled-up layer of carbon that are only one atom thick.

In addition, nanotubes have excellent electricity-conducting properties in sizes below 10 nanometers, a measure that appears to be smaller than any that can be achieved with current chip etching equipment. Even if smaller circuits can be built, they are approaching a density in the sub-10 nanometer range that makes technicians uncertain of the reliability of their electrical properties. Electrons might opt to jump circuits instead of staying on track.

But the sub-10 nanometer nanotubes have so far been impractical. To function as transistors, the tubes need to have effective electrical connections from their tips to the rest of a processor's components. IBM is saying it can now create that connection.

IBM makes the claims in an article appearing in Science magazine Friday, Oct. 2.

If what can be achieved in a lab can be produced in products, then cloud servers will suddenly be capable of much denser computing than any achieved with Intel or IBM Power chips, while consuming less power. Even more important, handheld and mobile devices would gain an exponential increase in compute power and memory while exhausting their batteries at a slower rate.

Nanotubes sip power the way a lizard lives off dew in the desert.

Changing Computing As We Know It

That means tasks that qualify as "big data" today could become more ordinary in the post-silicon era. A road warrior might never be more than one connection away from complete access to all corporate resources instead of being served up only contact information and a few sales charts. Conclusions hidden in reams of historical data and subject to data warehouse queries might be offered up quickly and visually to a mobile worker at a moment's notice. Researchers gathering fresh data in the field might at the same time process that data against large data banks, leading to new conclusions and new avenues of research on the spot.

The nanotube announcement is critical to IBM in another sense. The company sold off its last stake in silicon Power processor manufacturing to GlobalFoundries for $1.5 billion a year ago.

GlobalFoundries was to supply IBM with chips for the next 10 years, moving from 22-nanometer circuits down to 14 nanometers and 10 nanometers, the expected last hurrah for silicon chips. To have a continued future in servers, IBM needs a silicon replacement. If nothing else, that explains its periodic announcements on nanotube advances.

But IBM is also in the second year of its announced $3 billion-a-year, five-year investment in next-generation chip technologies. Over the next few years, it must either succeed in converting advances in the lab into reproducible components ready for mass fabrication or retreat from the server business. On July 9, it said it had produced the first 7-nanometer functioning transistors, in partnership with GlobalFoundries and Samsung at the State University of New York Polytechnic Institute's College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering in Albany.

Ten nanometers is estimated to be 10,000 times thinner than a strand of human hair. For purposes of comparison, 7 nanometers is slightly larger than one molecule of hemoglobin, estimated at 5 nanometers.

After breaking through the 10-nanometer barrier, "IBM's breakthrough in creating a new contact approach overcomes the other major hurdle in incorporating carbon nanotubes into semiconductor devices," said IBM's announcement on Thursday, Oct. 1.

The MIT Technology Review reported Sept. 25, 2013, that the first nanotube processor had been built by a group of Stanford University engineers with 178 transistors. It was equivalent only to an Intel 4004 chip produced back in 1971, but was meant as a proof-of-concept device. It could perform simple logic tasks such as sorting numbers or fetching data from a storage device.

Given their shrinking size, up to 2 billion nanotube transistors are expected to be packed onto a future CPU. Nanotube transistors can operate on less electricity and run cooler at much greater density than silicon circuits. Nanotube CPUs are estimated to use half the electricity of equivalent silicon devices.

Still, there's no large-scale fabrication process today that works with nanotubes. They are so small that what can be constructed in the lab may remain a challenge to move into a manufacturing facility.

[Want to learn more about IBM's nanotube research? See IBM Pledges Nanotube Transistor By 2020.]

Nevertheless, Dario Gil, VP of science and technology at IBM Research, wrote in this week's announcement: "This breakthrough shows that computer chips made of carbon nanotubes will be able to power systems of the future sooner than the industry expected."

IBM Research consists of 12 IBM labs around the world.

Years Away

The contacts at the tips of a transistor control the flow of electrons off the device and into the channels of a CPU. As transistors shrink to nanotube size, the amount of resistance represented by the contact point increases, impeding the transistor's performance. Simply decreasing the size of the contact hasn't worked.

IBM got around the problem by chemically bonding metal atoms to the carbon atoms at the ends of the nanotubes. It calls the process "akin to microscopic welding," the announcement said. The contacts allow nanotubes to achieve their full performance as semiconductors.

The nanotube CPUs may show up sooner than expected, but nanotube computers are still somewhere beyond the foreseeable horizon, IBM conceded. Its spokesmen would only refer to a timeframe "within the decade."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like