Why does calculating cloud ROI remain so tough? Examine the tactics used by two cloud innovators, GE and Airbnb -- plus our exclusive survey.

Read the entire Aug. 4 issue of InformationWeek — no registration required.

Read the entire Aug. 4 issue of InformationWeek — no registration required.

When it comes to judging the true cost of cloud computing, many companies try to break down the cost of running their own on-premises data center and compare that with the cost of using Amazon's or Microsoft's cloud. At Airbnb, Dave Augustine doesn't really have time for all that.

The six-year-old Web company has never had its own data center. Airbnb launched its service, which matches travelers with people looking to rent out a room or other accommodation, using the Amazon cloud, and its developers still build all their applications for Amazon's EC2. Having more than one cloud infrastructure provider, says Augustine, Airbnb's manager of site reliability engineering, "is an interesting idea" he might look at someday -- perhaps after Airbnb doubles its bookings again. As for determining his company's return on investment on Amazon services, Augustine calls that "penny-pinching."

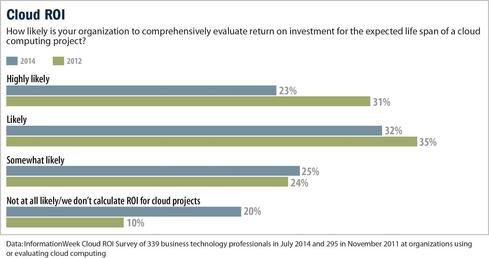

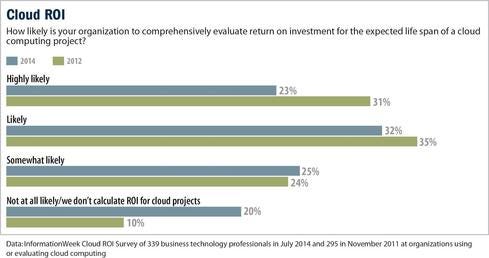

Augustine and Airbnb land in the minority of respondents to this year's InformationWeek Cloud ROI Survey -- the 20% of companies that don't calculate ROI for their cloud projects. The other 80% of the 339 companies using or evaluating cloud computing say they're highly to somewhat likely to calculate ROI for cloud projects. "Right now, we have better things to do," Augustine says.

While the 122-year-old General Electric also is "all-in on the cloud," says GE Cloud chief operating officer Chris Drumgoole, its approach is dramatically different from Airbnb's. Unlike Airbnb, the 300,000-employee GE wasn't born in the cloud and must find a way to migrate a massive legacy application infrastructure. GE operates 34 company-owned data centers and runs more than 9,000 applications. It's now consolidating to five data centers and painstakingly evaluating which applications it will rearchitect and move into a private or public cloud, and which ones it will phase out. It's also using software-as-a-service selectively, striking a deal in May, for example, to give employees access to Box online storage.

Figure 3:

And if you know GE, the king of managing through metrics, you know it's basing its cloud decisions on intense ROI calculations. Put GE among the 23% of respondents in our Cloud ROI Survey who are highly likely to calculate ROI.

[Read related stories: Cloud ROI Easy Win: Disaster Recovery and Milliman Strives For ROI With Azure System.]

But cloud ROI calculations are difficult, even for a company as steeped in analytics as GE. Unlike Airbnb, GE wants multiple cloud infrastructure providers; it's using Amazon and Microsoft Azure today, and it plans to use Verizon's cloud. "We envision a world metric that measures application performance" across vendors, Drumgoole says, but such a measure won't be possible until GE has at least a year of captured experience, and probably several years' worth.

Figure 4:

The stories of Airbnb and GE reflect the reality of cloud computing technology. Operationally, cloud technology has proved itself capable of handling large-scale infrastructure and software needs. Financially, however, companies still are struggling with the right way to calculate the payback; how to measure the cloud's value in speed, cost, and staff focus; and how to assess where cloud use makes the most sense.

The responses to InformationWeek's Cloud ROI Survey reinforce that uncertainty. Some notable findings:

-- At least half of survey respondents consider these three financial factors among their top cloud ROI priorities: initial capital costs, operational expense,

and future capital costs. A third of respondents consider staff savings a top-three priority.

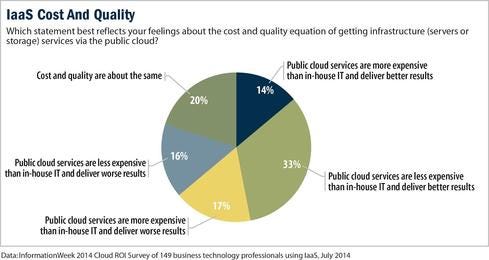

-- One third of respondents using infrastructure-as-a-service say it delivers better results at lower cost than in-house IT, and 20% say they're equal. The rest (47%) say IaaS costs are higher, the results worse, or both.

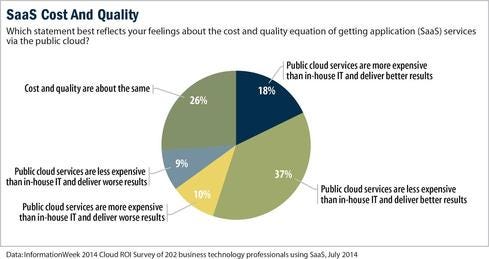

--For software-as-a-service, 37% of users say it delivers better results at a lower cost than in-house IT, while 26% say they're the same. That leaves 37% who believe costs are higher, results worse, or both.

--Forty-five percent of respondents whose companies use cloud computing say they have a formal policy or stated preference to evaluate cloud for any new application, while another 38% say their companies are headed in that direction.

--Fifty-two percent of companies say they're using SaaS, up from 40% in our Cloud ROI Survey two years ago. IaaS use is up to 38%, compared with 25% two years ago.

What's clear is that cloud use is growing fast, even as the ROI calculations for it remain complicated and fuzzy. What follows is a deep dive into how two companies, Airbnb and GE, are thinking about cloud computing, with additional survey data on how other companies are approaching ROI calculations.

Airbnb: Born in the cloud

Since its founding in August 2008, Airbnb has gone from an idea that couldn't possibly work -- helping people rent out their apartments and vacation homes to total strangers over the Web -- to a business that executes 4 million bookings a year. Today, Airbnb, despite the occasional bad PR about a trashed apartment and looming regulatory concerns, is making it work. When soccer fans traveled to Brazil for the World Cup, for example, 120,000 of them booked rooms through Airbnb. Private room owners serving as hosts pay a 6% to 12% booking fee, plus 3% for completing the credit card transaction.

[Read related stories: Cloud ROI Easy Win: Disaster Recovery and Milliman Strives For ROI With Azure System.]

What started out as three air mattresses leased out of its founders' loft has grown into a business valued at $10 billion by its venture capital backers in April. In 2011, when Augustine started with the company, it used 20 to 30 nodes on Amazon's EC2 cloud service. Now it's somewhere north of 1,000.

Figure 2:

The cloud's value to Airbnb is its ability to let the company scale up its capacity quickly for the next round of business expansion. Under its "Belong Anywhere" rebranding campaign begun in mid-July, Airbnb is trying to shift its image, from being an impersonal way to find a room for a trip to being the means of finding just the right host and unique lodging experience. As part of the campaign, hosts and travelers can customize and share the new Airbnb "Bélo" logo -- so a host can change the colors and use it as wall art in the room they rent, for example. The company set up a new website, Create Airbnb, for that campaign. Augustine prepared Airbnb systems for a doubling or potential tripling of traffic, and he had less than two weeks to gear up for it.

"We talk about it all the time internally -- our speed to market and how important it is," Augustine says. "It's incredible how fast our internal systems can be built out." Being able to quickly increase the number of Amazon Web Services' large C3 servers using automated scaling makes right-sizing the infrastructure quite a bit easier than it would be with in-house servers. That kind of automated scaling -- letting Amazon add servers to meet whatever demand comes -- scares some cloud customers, because it could lead to runaway costs. In the InformationWeek Cloud ROI Survey, 89% of respondents using or evaluating cloud computing say they're somewhat concerned, concerned, or very concerned about runaway cloud costs. At Airbnb, that worry takes a back seat to meeting customer demand and quickly testing new initiatives.

Airbnb has 100 software engineers creating and supporting booking, marketing, and engagement systems. For IT operations, it has only four to eight people, because it's not actually running the data center and related hardware. With only that handful of ops staff, Airbnb has expanded into Australia, Asia, and Europe, buying up a German competitor earlier this year and expanding its own European services. "If we had to build our own infrastructure, it wouldn't have happened so fast," Augustine says.

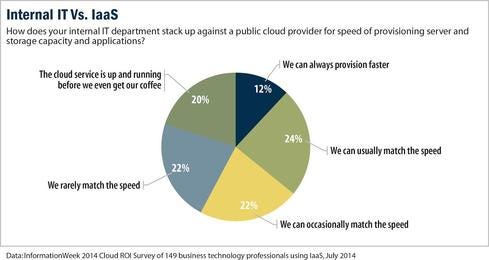

In our Cloud ROI Survey, respondents give cloud a clear advantage in speed of delivery. Only 12% of respondents using IaaS think their IT organization provisions infrastructure faster than a public cloud service, while 24% say they're comparable. That leaves 64% saying the cloud is usually faster.

Airbnb isn't oblivious to cloud costs, even if its executives aren't interested in the specific details of cloud ROI. Airbnb can take that lax attitude in part because cloud providers keep cutting their prices. In March, Amazon announced its 42nd price cut since launching its AWS cloud service, reducing the price of its M3 servers by 38% and its Simple Storage Service by 68%, a move that followed equally steep cuts by Google for its Compute Engine and Microsoft for Azure. Companies like Airbnb that had justified adopting cloud services at earlier pricing levels now have even less interest in ROI metrics.

"Forty percent is a huge number. That definitely made a big difference in our bottom line," Augustine says.

GE: Cloud gets more complicated

Most business technology leaders will look at Airbnb with envy -- no legacy applications and infrastructure, and a business built around a single online function. On the opposite end of the legacy IT spectrum is GE, whose businesses span jet engines, medical devices, locomotives, power plant

turbines, appliances, and financial services. As GE moves to a cloud infrastructure, Drumgoole knows he can't force one way of doing things on each business.

"Our view is, we build the roads," he says, including private and public cloud infrastructure. "The businesses units have to decide what they want to drive on them."

GE spends "millions" a year on public cloud services, Drumgoole says, in part because it wants to understand that architecture as it looks to design its own future data centers with cloudlike characteristics. GE plans to reduce its 34 data centers to "less than five" in the next few years.

But GE's calculations for using the public cloud are far more complicated than "which is cheaper, public cloud or in-house?" One factor is whether the data that the application uses can be stored safely in the cloud. For sensitive personal and transaction data, "Amazon can't handle that today," Drumgoole says. "Someday, no problem, but not today."

Figure 5:

Which raises the question: Which metrics does GE use to decide on a public cloud service vendor? It uses an instance base model -- a virtual machine with a certain amount of CPU, memory, and storage -- to compare services, but Drumgoole says that's only part of the evaluation. There's also the question of whether the supplier provides solid state disks, the rate of input/output operations per second (IOPS) it supports, and the size of the network pipe running application-to-application or application-to-storage.

[Read related stories: Cloud ROI Easy Win: Disaster Recovery and Milliman Strives For ROI With Azure System.]

Each supplier defines a virtual instance a little differently. When it comes to IOPS and networking, the variances are even greater, Drumgoole says. Cloud ROI comparisons are difficult, but GE, with its far-flung global operations, wants many vendors. "We would like to see more players," Drumgoole says. "We're not as U.S.-centric as some companies."

GE takes an application-centric approach. With so many legacy applications, its challenge is less about choosing one cloud vendor and more about rearchitecting its software for future cloud use. Drumgoole has no interest in moving legacy applications as is into the cloud. He wants to build more generalized services that will reduce the total number of applications he must maintain, cut the number of technologies he's dealing with, and radically simplify the environments for which he's developing future applications.

Drumgoole notes that getting the first 100 applications into the cloud was painstaking. Some of the 9,000 will be rewritten; some will be eliminated as new services are brought online. Migrating many of the remainder will go faster, he says, but it still won't be easy. Most companies are taking the long view in evaluating the ROI of cloud projects, our survey finds. Just over half of respondents at organizations likely to evaluate ROI look at a three- to five-year period, while 30% consider two years or less.

By the time GE is down to just five data centers, it will have selected a standard cloud server design after "a vigorous intellectual debate going on right now," says Drumgoole. That server design will be built by an independent hardware manufacturer, in much the same way that Fidelity and Goldman Sachs are using hardware designs shared through the Facebook-backed Open Compute Project.

Figure 6:

GE, like Airbnb, doesn't see cost savings as a primary driver of its migration to cloud services. Likewise, only one in five respondents at organizations likely to evaluate cloud ROI say it's the only or most important factor. Still, 70% say it's important, while just 10% say it's a minor factor or not at all a factor.

Unlike Airbnb, GE knows that some of its resources will be in its own private cloud data centers as well as in public clouds.

Most big companies will live in this hybrid private-public cloud environment for years to come, but it's a difficult path to navigate, given the pricing complexities. GE wants to build a standard set of services and a private cloud environment in which they will run. In Drumgoole's view, IT in the future will tell each unit, "Here's a machine-readable service catalogue" and leave it to each unit to make use of it.

GE's approach leaves some elements of the cloud ROI assessment to be handled down the road by the company's line-of-business managers, as they apply a range of cloud metrics to their specific needs -- a similar scenario most companies will face.

Read the entire Aug. 4 issue of InformationWeek --

no registration required.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like