Organizations such as NASA and Google continue to invest in quantum computing even while questions are asked about whether it exists. Can a company called D-Wave deliver?

Data Visualizations: 11 Ways To Bring Analytics To Life

Data Visualizations: 11 Ways To Bring Analytics To Life (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

NASA, Google, and the Universities Space Research Association have announced that they have renewed their contracts with D-Wave, a Canadian company that has developed computers that, it claims, solve the problem with computers.

There is great debate about whether they've succeeded and tremendous interest in the outcome of the debate.

The problem with computers is that they're so-o-o slo-o-ow. Not when it comes to work processing, necessarily, but if you're trying to model a fundamental state of the universe or the action of a complex drug interaction, the fastest computer can seem like Blue Molasses.

That's why so many organizations are interested in installing a computing system that might or might not do what it claims in order to produce results that might or might not be correct.

All this uncertainty is part and parcel of quantum computing, a computing architecture that depends on the state of quantum bits -- or qubits -- rather than the familiar 1 and 0 of classic binary architecture. In theory (and much of quantum computing is still theory) a quantum computer will calculate every possible answer simultaneously.

The problem comes when you try to figure out what that answer happens to be.

As anyone who's ever pondered Schrödinger's Cat knows, all of those possibilities exist until you open the box -- or ask the computer for an answer. At that point, all the possibilities collapse into one answer -- an answer that has at best a statistical probability of being correct. Most quantum computing architectures will run through an equation multiple times to see which answer comes up most often, but as you drive toward certainty, you drive away from the speed advantage provided by quantum computers in the first place.

In order to get to any answer, some very special conditions must be created.

[Read more about data-centric supercomputing.]

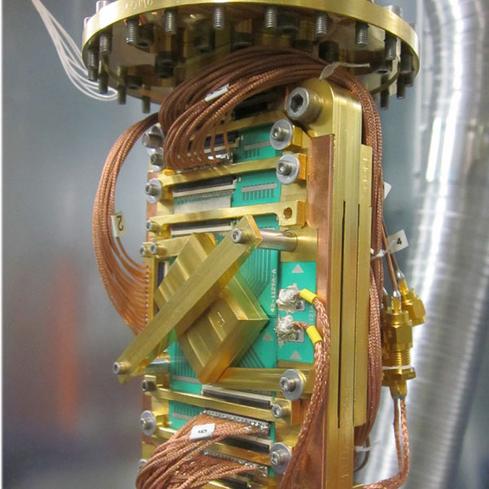

Quantum computers need to be heavily shielded to avoid interference from cosmic radiation and "noise" in the form of all the vibrations, emissions, and emanations of modern society. They need to be cold -- just barely above absolute zero -- in order to slow atoms down enough to allow them to be herded into order and structured into qubits.

The housing for a D-Wave qubit.

There is great debate among engineers about whether the D-Wave computer is actually a quantum device. Scientists at IBM have been especially vocal in their suspicions that D-Wave is actually a rather normal computer under the hood. The trouble with figuring out the answer is that you can't just open up the electronics and watch the process. Opening the hood takes us back to Shrödinger, only now the statistical waves are collapsing at the wrong time.

With all the problems, why pursue quantum computing and write checks for a solution that might or might not be the solution you're looking for? The first reason is the speed mentioned at the top of this article. The other is that quantum architecture allows researchers to use computers to solve problems that are structurally unsolvable by classic, binary computers. There are a fair number of those problems out there and many people would love to see them finally solved.

Organizations will continue to spend money, scientists will continue to build qubits, and cats will continue to be both dead and not-dead until the box is opened. Because absolutely no one likes a slow computer.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like