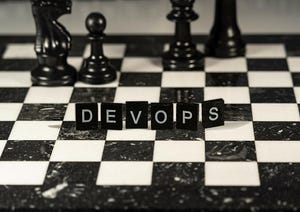

DevOps

News, expert knowledge, and case studies for IT executives about application development trends such as no-code / low-code and DevOps-related practices and strategies. Explores the benefits and tradeoffs of using “citizen developers” who are backed by automation and platforms to produce certain applications versus professional developers fulfilling such duties. Explains how different branches of a business, such as security and operations, can influence application development strategies.

Young concentrated computer developer writing new code

Software & Services

How Developers of All Skill Levels Can Best Leverage AIHow Developers of All Skill Levels Can Best Leverage AI

As AI evolves, developers across the board should use coding assistants wisely. Regardless of their experience, it’s important to remember that AI can’t replace human critical thinking or review completely.

Never Miss a Beat: Get a snapshot of the issues affecting the IT industry straight to your inbox.