CyArk is on a mission to preserve detailed 3-D scans of every site on the Unesco World Heritage Site list. It's a race against disasters, both natural and man-made.

8 Ways You're Failing At Data Science

8 Ways You're Failing At Data Science (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

Things fall down. So says the second law of thermodynamics and pretty much every sane civil engineer. Trees fall in the forest, whether we hear them or not. Buildings large and small eventually crumble. But sometimes the things that might fall down are important artifacts in human history and culture. That's where CyArk comes in.

CyArk was founded in 2003 to preserve the knowledge of culturally important sites for future scholars while making many of those sites accessible to those who might not be able to travel today. CyArk does this by making detailed 3-D scans of the sites and creating "point clouds" from the resulting data. The resulting projects, like the Temple of the Feathered Serpent at Xochicalco in Mexico, allow scholars and interested individuals to see the site in great detail and plumb information about the site to depths that vary from project to project.

Scott Lee is director of operations at CyArk. An architect by training, Lee was eager to share details of how CyArk accomplishes its mission on a Skype call with InformationWeek. The picture that emerged was of an organization that uses trained professionals within the organization, data volunteered from professionals that support the organization's goals, and contributions from corporate partners to capture, analyze, and safely archive the information from as many culturally important sites and artifacts as possible.

"We have roughly 208 projects from seven continents currently archived," Lee said. He explained that the detail of the data and the incoming data format depend on the demands of the site and the needs of the crew performing the survey. "We're capturing sites from three millimeters to sub-millimeter levels of resolution," he said, explaining that the differences depend both on the nature of the site (including the size of the most detailed portion of the site) and on the equipment available to do the mapping.

Regardless of the level of detail, Lee said that the organization ends up capturing seven bits of data for each point that's mapped. "Our bread-and-butter data are X, Y, and Z coordinates; R, G, and B for color; and I for intensity. So there are seven pieces of data we store," he said. As for format, Lee said that CyArk has decided that plain ASCII text is the format likely to have the broadest, longest life span, so that is how all the data is stored.

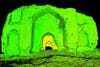

A 3-D scan of the Timurid Pavilion, a remnant from the Timurid Empire, a late 14th century CE Turko-Mongol Dynasty in the remains of ancient Merv.

Those seven pieces of information can add up when an entire site is considered. "It's a text document that has the seven values for each point, with up to 22 billion lines of data," Lee said. Given that many of the sites are in areas of conflict, the question becomes how to then get the data back to CyArk's headquarters. The answer, as with many of CyArk's technical issues, is "it depends."

"Sometimes the data sets are multiple terabytes, so it's dropped onto a hard drive," Lee said. "Sometimes it's FTP; sometimes, for a smaller file, a thumb drive." No matter how the files are delivered to CyArk's California headquarters, once there they are processed and normalized to make them useful to scholars and engineers. Some, like the Monastery of Geghard, are developed as projects placed online to make them accessible to students and the public. All projects are then stored on redundant disks for security.

.jpg?width=100&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

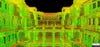

Rani ki Vav is a stepwell commissioned by Udayamati as a monument to her husband, King Bhimdev I, who ruled Gujarat and neighboring Rajasthan for more than forty years, from 1022 until his death in 1064.

"Once the data gets to us it goes directly on our server in-house. Later that night it will be backed up to a tape system," Lee said, explaining that CyArk has two systems for backup, each with its own purpose and priority. The main archives are held on Commvault and Strongbox systems, Lee said. "Strongbox makes it look like a NAS [network attached storage], while Commvault is compressed," he added. "The Strongbox system is a Windows file system and ASCII files, and that's done on a monthly basis."

When asked about how much of the data is kept "live" on the CyArk server, Lee talked about online and offline storage. "A lot of the data is still on the server -- we have about 200 terabytes there. The rest is on tape and we can pull it up quickly. We have three tape copies: One on-site, one with Iron Mountain, and one in Iron Mountain's ultra-secure site," he said.

The security of three versions is critical because of the damage being done to world heritage sites. "In the last decade we've seen so many sites destroyed. Even in the last six months there have been so many sites damaged, so many archeologists killed," Lee said. "Project Anqa is where we are trying to document so many of these sites before they're destroyed. We had a team survey the Ziggurat of Ur, and we're launching an initiative to document as many sites in the Middle East as possible."

A 3-D scan of Rani ki Vav facing east.

All of this is done by a small staff numbering a dozen or less. Further, it's done by a staff that owns practically none of the equipment taken into the field by its teams. "We're fairly agnostic, and technically don't own equipment at CyArk. [Vendors] will loan us hardware for our projects," Lee said. "A lot of the vendors like to see their equipment on the sites, so we get to use the latest and greatest equipment."

The same is true for much of the storage used for CyArk projects, and the storage expertise required to build reliable archival storage systems. "We really lean on our network of partners, because our mission is very ambitious. Companies like Seagate act as free consultants and let us lean on their expertise."

A small organization with a large mission, CyArk demonstrates the importance of partnership for successful IT. The question of whether in-house expertise is superior to partner talent is nearly moot when the in-house talent pool is so small compared to the work to be accomplished. For CyArk, the race is real to scan and protect, before the forces of nature and man make treasured sites fall down.

**New deadline of Dec. 18, 2015** Be a part of the prestigious InformationWeek Elite 100! Time is running out to submit your company's application by Dec. 18, 2015. Go to our 2016 registration page: InformationWeek's Elite 100 list for 2016.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like