Companies may have to reshape how data is interacted with and monetized as legal upheaval and uncertainty about data privacy take hold.

Gathering customer data from devices, web traffic, and apps has long been central to operational strategies at startups and enterprises alike. Can and should those data strategies continue after the dismantling of Roe v. Wade?

In the weeks since the US Supreme Court upended nearly 50 years of legal precedent, questions continue to be asked about the collection of personal data that might implicate users in states that institute laws to ban abortions. Initial concerns pointed to apps used to track menstrual cycles, but what about beacons and other technology that can track where a user travels? Would a company have to turn such data over to local authorities?

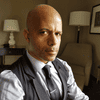

“This isn’t just about period tracking,” says David Ruiz, senior threat content writer with Malwarebytes. “This is about location data, too. This is about if you visit a Planned Parenthood. Should that data be available to someone else?”

Waking Up from Data Complacency

He says the world experienced a decade where companies saw collecting as much data as possible as the right and smart thing to do. “It could help them target users; it could help them tell users activities about themselves,” Ruiz says. Now companies need to ask what they need the data for, he says, with laws such as General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union setting the tone for only collecting necessary data for services being offered.

The overturning of Roe v. Wade may be another motivation to follow such guidance, Ruiz says. “We're already seeing quite a few businesses, particularly period tracking apps, making a sudden pivot.” Some apps are releasing "anonymous" modes; therefore, if law enforcement requests information, that data will be unmeaningful for identification. Some companies are looking to end-to-end encryption of user data, he says, to keep it out of the hands of law enforcement.

Ruiz says most changes that are to come to the market will likely affect companies that work with highly personal data. He cites public responses to crises such as the data collection practices of Cambridge Analytica prompting some users to give up Facebook. Changes in privacy policies at WhatsApp, Ruiz says, also led to some users moving to alternate apps.

Data Privacy Redux

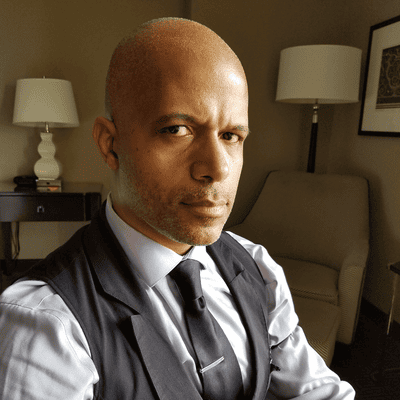

The Supreme Court decision pushed data privacy discussions to the forefront once more, says Christine Frohlich, head of data governance at Verisk Marketing Solutions. “Those of us who have been working in the data industry have been thinking about this for a long time,” she says. “The regulations we’re seeing in California, and now what we’re seeing in Colorado, Connecticut, Virginia, and Utah have made this a real hot topic within our industry.”

Companies have a fundamental responsibility, Frohlich says, to protect consumer privacy to the best of their ability. Customers may enjoy personalized experiences such as a digital interaction with a brand or having products marketed to them in a personal way, but she says they are also concerned about how their data is used.

Federal legislation on data privacy might move forward faster in response to the Supreme Court decision, Frohlich says.

The “right to be forgotten,” or a deletion requirement is flowing through state legislation and what is being proposed potentially on a federal perspective, she says. “That is an aspect of consumer privacy that data companies are going to deal with. Regardless of what’s happening from the Supreme Court decision, we know we have to manage to the ‘right to be forgotten.’”

Changing Data Business Models

Frohlich says the industry should respond with transparency and giving consumers the option so they know they can opt out or can ask companies to not use their data for certain types of use cases. Some businesses may struggle to adapt, she says, which could show the difference between mature companies that have strong data governance practices versus companies that just have a business plan centered on grabbing data. “That no longer will be a sustainable business model moving forward,” she says.

Companies that can secure trust with consumers should be able to manage through these times from a privacy perspective, Frohlich says. Ensuring that precise location data is used appropriately, she says, comes down to companies knowing what data they are collecting and how long they are retaining it. “We should not collect data that we do not need for a very specific business purpose, and we should not be keeping it any longer than we should.”

New Categories of Sensitive Data

Data deemed sensitive in terms of state and federal legislation currently includes health information and soon may add new categories such as precise geolocation data and financial data, Frohlich says.

Digital commerce can make it increasingly challenging to conduct business without leaving data behind, especially with apps, platforms, and resources that require email addresses or social media identities to access them. Many consumers get pop-ups about cookie collection at websites or when signing into an app, Frohlich says, and have been comfortable signing up for such data collection. “I expect that will continue. Where I see the change is that those app and service providers will have to be far more clear.”

Pay models may rise as an alternative, she says, that some online services and apps might move to as they walk away from monetizing data as their primary economic model.

Uncertainty of how state laws may play out in the future emphasizes the importance of federal privacy regulation to become part of the equation, Frohlich says. Her team is engaging in a robust data inventory to know what every piece of data is that the company collects, how it is categorized, and how the use cases are understood. “We’re in a situation where consumer data privacy is regulated at the state level, so it’s incredibly fragmented,” she says.

What to Read Next:

Businesses Grappling With Post-Roe Data Privacy Questions

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like