Shoebox-sized Dove satellites capture ongoing high-resolution images of earth from small, low-cost satellites.

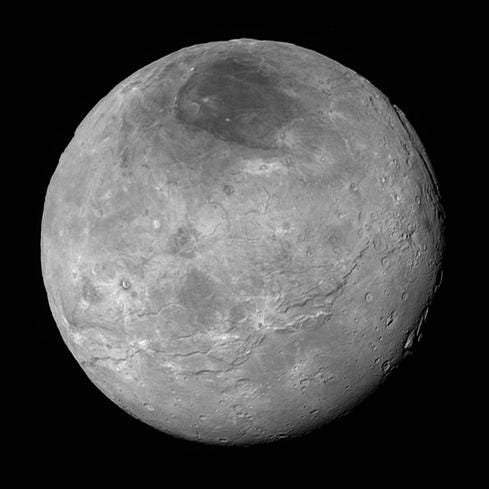

NASA's New Horizons Transmits New Pluto, Charon Images

NASA's New Horizons Transmits New Pluto, Charon Images (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

Planet Labs CEO Will Marshall wants to give researchers, scientists, farmers, traders, and any other interested parties access to real-time data about planet Earth. Most satellite imagery is weeks or months old. He thinks it's time to bring the earth's surface data into frequent update mode, meaning every 24 hours.

Marshall, a former NASA scientist, and his team plan to get a fleet of 150 of his firm's Doves -- miniature, camera-bearing satellites -- into orbit sometime next year -- more satellites than all the other launchers combined. So far, the company has launched 100 of them.

"We are getting to the point where we can image the entire earth in a day," said the young, bespectacled CEO, who looked like he was only a few years out of graduate school as he spoke Tuesday, Sept. 15, at a morning talk during Salesforce's Dreamforce user group event in San Francisco.

Most image-collecting satellites are like Landsat 8 -- a monstrous box of cameras, gyro-compasses, transmitters, and other equipment weighing 5,783 pounds. Landsat 8 was launched by the US National Geological Survey two years ago as part of a long line of Landsats.

[Want to learn more about use of satellite imagery in search missions? See The Search For Microsoft Researcher Jim Gray.]

A Planet Labs Dove, on the other hand, is about the size of a shoebox, weighs 8.8 pounds, and still contains the high-resolution cameras and other equipment that Landsat has, except in miniature.

At Dreamforce, Marshall talked about how a revolution in lower-cost satellites and satellite imagery will change how we capture changes in the earth's surface, agricultural data, and other business information. Doves are "hundreds of thousands times cheaper" than $750 million Landsats and earlier generations of satellites, he said. He showed pictures of the first Dove being hand-assembled in a garage. They're now assembled in the basement of Planet Labs' San Francisco headquarters.

With cloud computing, high-volume storage, and cheap satellite imagery, many people are going to have access to data on how a specific surface area is changing, of "a connected, big data, transparent planet," he said at Dreamforce. It may even change how we view the planet, he suggested.

Are global ice caps shrinking? Planet Labs will make it common knowledge. Are soybean crops in trouble around the world? Commodities traders may be among the first to know. Rainfall, weather patterns at sea, and forest-fire movements may all become imagery information available at a person's fingertips. After the Nepal earthquake in April, Planet Labs imagery showed rescue workers the location of two mountain villages that they didn't know existed. A good day's work, as far as Marshall was concerned.

Planet Labs has $183 million in venture capital to finance its satellite network, as well as several paying customers, including agribusiness firm Wilbur-Ellis.

{image 1}

Planet Labs will ask just about anyone going into space to take a Dove or several Doves along for launch once they get there. "We asked the astronauts to toss them out the window" from the International Space Station, Marshall quipped. Two were launched that way, and he showed video of that happening at his Dreamforce session.

Not all of them have made it. Two rockets have blown up before achieving orbit: One incident happened on Oct. 28, 2014, when Orbital Sciences Corp.'s Antares rocket at NASA's Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia blew up on the launch pad. The other failure was Elon Musk's SpaceX rocket, which blew up June 28 in the subspace atmosphere. Twenty-six Doves were lost in the former, eight in the latter.

Nine launches have made it, and left 100 Doves in orbit. Sometime next year, the company wants to have those 150 Doves recording imagery and sending it to ground-receiving stations for aggregation by Planet Labs.

Planet Labs will direct each Dove to photograph a narrow band of the earth's surface. Then all the bands will be assembled to build a composite picture "like lines from a line scanner," he said. The information will be available for purchase and use, for instance, by farmers checking their crops in the field, shipping firms tracking the arrival of their vessels in port, and foresters trying to prevent illegal cutting of forests in remote areas.

During his talk, Marshall held up one of the small, rectangular satellites that appeared to be worse for wear. It was still functional, but Marshall explained it had been onboard the Antares rocket when it exploded. The satellite was launched on a brief flight through the lower atmosphere near sea level, where it traveled several hundred feet to land on the beach.

The satellite was acting as if it had been launched into space and was "trying to phone home, but unfortunately there wasn't a ground station anywhere near the launch site." The satellites are ruggedized, since they must survive a 200G jolt when the first stage of the rocket falls away and a second ignites. Getting into orbit requires traveling at 10 times the speed of sound. The jolt is the equivalent to being dropped from eye level to a marble floor, and the camera lens must not vary its position by more than a few microns, he said.

Planet Labs is one of several firms venturing into the business of big data from space. Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon.com, has launched Blue Origin. Google, which acquired Skybox for $500 million, is working with Fidelity on its own network of satellites, possibly to provide Internet service to remote parts of the world. In addition to the well-known SpaceX and Orbital Sciences Corp., there's the 2012 startup Spire Global.

A pixel in an image from the new generation of satellites can capture an object 3 to 5 meters large. Marshall said even finer resolution is possible, but would begin to allow cars, people, and other objects to become recognizable. Planet Labs didn't want to set off a storm of privacy concerns.

"By taking images of earth every day, I hope humans will be better able to take care of our beautiful, spaceship earth," he said.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like