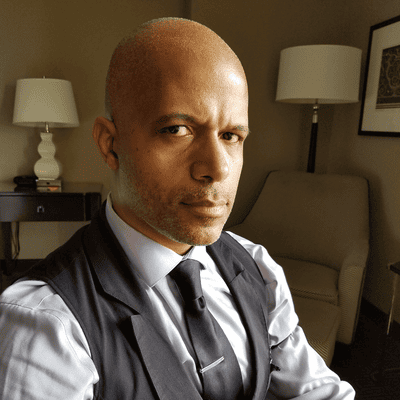

Jamie Holcombe talks about developing a “software factory” drawing upon DevSecOps methodology and GitLab to help it modernize software development within his agency.

Even the federal agency that puts its stamp on new, original innovations has had to update its infrastructure using DevSecOps for a cloud-based world.

United States Patent and Trademark Office dealt with a software system outage in 2018 that disrupted the patent application filing process and exposed a need for more effective data recovery. The downing of the Patent Application Locating and Monitoring system, which tracks progress in the patent process, along with other legacy software applications, helped prompted changes at the federal agency.

Jamie Holcombe, the USPTO's Chief Information Officer, spoke with InformationWeek about taking advantage of modern resources such as GitLab along with DevSecOps methods to improve time delivery on IT updates, shifting to the cloud, and improving resiliency.

What was happening at the USPTO that drove the changes you made? What was the pain point?

What was the burning platform? Why did you have to jump off into the sea because everything around was just going to hell? Well, what had happened was, before I even arrived at the agency, the Patent and Trademark Office experienced an 11-day outage where over 9,000 employees could not work.

Why couldn’t they work? They were using old, outdated applications -- which is okay; everybody uses old apps -- but they didn’t practice on how to come back and be resilient. When they took out those backup files to lay over the top and bring the database up, they didn’t know how, and they failed not once but twice.

The third one they were able to lay over the top and got back continuity of operations. The only problem was it was 9 petabytes of information and they had failed to back up the indices of the database. So, it took over eight days to rebuild the indices. That’s a lesson learned.

That was the burning platform. Then there were a lot of complaints by the business that IT was slow and “You can never deliver on the new stuff.”

Well, I’m sorry when you’re trying to attach a flame-throwing or a very fast car on an old platform. It’s very, very difficult. I compared it to a Model T Ford with a Ford F-150 -- you just can’t put them together; they don’t work. There was a real need to change the underlying platforms.

The ingenuity involved in making that Model T act like a Ford F-150 is phenomenal. These guys are really competent and great at what they do, but you can only do so much with so little.

Once you were confronting this situation, what was the process for taking the next steps? In the private sector, someone in the C-suite will make decisions. What steps, as a government entity, did you need to take to get things going?

I do come from the commercial world. Although I started out my career in the military, I soon went over to the intelligence world, which has a lot of advanced technologies, then I went into the commercial world -- I got back into the government, then I went commercial, and then I went government. I’ve been in and out of the government from the commercial world.

One of the things that I try to bring in is the newness, the ability to take advances in technology and implement them for what’s currently existing. So, the process is very commercial. You got to figure out where you are, take your inventory. You got to describe where you’re going to go with the vision, and then you’ve got to describe the map -- how to get from here to there. During the inventory process, what I found out -- very competent people, very old technology. The vision was to create the ability to move from the old into the new using the cloud as our primary goal, our target.

There are some mainframe applications that just were not meant for the cloud. But the biggest thing that happened was we weren’t able to operate in a contingency. You can’t just move all these old apps into the cloud and expect it to work. We should have learned from our backup problem. Let’s not just have a hot-cold situation. Let’s create the vision that we have a hot-hot situation so that we’re able to run and one of the sites goes down, no matter. The other site’s running. We might have a degradation of performance but that doesn’t mean you still can’t get on.

When we tried to actually do that with the equipment that we had -- womp, womp, womp -- it did not work. It failed miserably. We did not have the compute. We did not have the storage. Nor did we have the bandwidth.

One of the big things was to get a new data center that was up to speed for the Internet Age. That’s what we’ve done over the past three years. We’ve been able to create a new data center for the old applications that we need to be on-prem.

We have gone over the last three years and put about 33 - 34% of our 200 applications out in the cloud. We’ve also moved now over 43% of our old applications into the datacenter so we have a hot-hot operation. We’re not there yet, but we’re almost there.

We had to really change the culture because although people had a great client server architecture background, the way the cloud works is a lot different. Asynchronous, concurrent programming is a lot different than the old client server, fat client networks. I’m not saying we don’t have fat clients -- it’s tough. We’re trying to move toward a more edgeless application suite. We’ve taken the old, integrated ERP. That’s exactly why when one application fouled up, all the other ones didn’t work.

One of the visions was to ensure that if one application went down, it wouldn’t cascade to the others. That is the microservice when you stave off a full stack and then use that separately and apart from all the other processes.

How we did that was we eliminated the project management office -- how does a government agency do that? You create the product category environment and instead of having fits and starts, starts and stops with the projects we do every year, you just continually have the same products moving over and over.

We have integrated project teams on our product side. They run agile DevSecOps. That “Sec” needs to be in there -- you need to have that from the beginning.

That was another vision to get out of our cybersecurity vulnerabilities by having everybody responsible for their own security.

How did GitLab resources become part of your modernization process?

There’s a lot of goodness in using GitHub and GitLab. The thing about standardization and the ability to have one place to go to and to trust that open-source part. We have our own, with our change control and version control, but without that type of management and standardization, you’re not going to get the throughput for automation that you need. You can pick different containers. You can pick different ways to put the CI/CD pipeline together, but you always have to have the common base to pull from, that foundation, that change control, that version control.

What we loved about [GitLab] was the fact that we can use it very efficiently but also very flexibly. We don’t have to adapt all the time. We can use what we’ve created before.

Before we might have put out a major version in six months. We’re doing it now every quarter at least, if not two or three times a month.

What are the current trends and forces that your agency must deal with in terms of the way technology is evolving? Software development is changing, and AI is making headlines. How has this affected the way you work or what you focus on?

The hardest thing is to take emerging technologies, not bet the farm but at the same time have enough understanding of the ability for these pros and cons, whether or not they’ll work for you or your business, then to scale it.

In all of our emerging technologies, we have to first prove the benefits that it works. The pros and cons will be developed and determined during that first 30-, 60-, 90-day period. Once that’s complete, once you know that it works, then you have to go to the next stage, which is scaling. Scaling is a lot different than just proving pros and cons. It might not be able to scale based on the fact that compute, storage, or bandwidth is just not there. So, you really have to do your scaling model.

Finally, the third step in the deployment, is get an executive champion to take the risk of putting it into production fully.

We have a huge portfolio of artificial intelligence and machine learning. Everyone’s getting a little more sophisticated in AI. We’ve taken machine learning to a different level. We’re doing that in our classification of our patents as they come through. It’s enabled us to release many of our old contractors.

We still have people look at the exceptions to ensure that on the feedback loop it actually is improving that precision instead of creating chaos. We have over 600,000 applications every year. There’s some set of a couple thousand that are probably exception based. Even though we have 94-95% precision, we still have 5% that we have to deal with on a human level. We’ve improved but there’s always more room for improvement.

What to Read Next:

Spotting DevSecOps Warning Signs and Responding to Failures

Is It Time to Rethink DevSecOps After Major Security Breaches?

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like