Could open-source hardware shake up the datacenter the way Linux disrupted software? From Facebook to Fidelity, a few big companies say this concept works.

Read the whole

Read the whole

Feb. 3, 2014, issue of InformationWeek,

distributed in an all-digital format (registration required).

Facebook, Fidelity, Goldman Sachs, and other leading IT users think the open-source movement is ready to shake up the hardware industry the way Linux did in software.

In the past, only the very biggest companies -- the likes of Amazon, Google, and, yes, Facebook -- could afford to customize servers, storage, and networking systems to their precise needs. Instead, most companies have filled their datacenters with off-the-shelf, mass-produced hardware from the likes of Hewlett-Packard, IBM, Dell, Cisco, and Oracle.

But an open-source initiative called the Open Compute Project is trying to upend this hardware production process in two ways simultaneously. First, Facebook and other companies are sharing their hardware designs through OCP. Such sharing could put leading-edge designs in the hands of many more user companies. Second, shared hardware specs let IT organizations mix and match parts from different suppliers, which opens hardware manufacturing to new players. As a result, open-source hardware could produce significant new competition for existing hardware vendors -- and a new bargaining chip for buyers.

Open-source software such as Linux, Apache, Python, and Android rewrote the rules of the software industry. With open-source code, any company can take, say, a Linux operating system and alter it exactly for its needs. Linux by no means put an end to proprietary Windows server software in datacenters, but it made for fierce competition (and for a while, considerable anxiety in Redmond). Open-source Apache software, meantime, became the dominant web server software. Android is now the market-leading operating system for smartphones just six years after Google launched the open-source OS.

Open-source hardware, on the other hand, still has everything to prove. Is Open Compute at the cusp of doing for hardware what open-source code did for software -- make a valuable technology asset available to a much broader set of developers and users, while lowering the usage costs? Or is the project caught in a cloistered community, one that helps Facebook burnish its image as a tech innovator while benefiting only a handful of financial services and other companies with massive computing needs and tech-savvy staffs?

Fidelity is among the true believers. The investment giant is rebuilding its IT operations around a private cloud datacenter architecture, and it's embracing OCP-inspired hardware as part of that change. OCP designs now account for a third of Fidelity's servers, and George Brady, executive VP of IT, expects that figure will grow to 80%. HP and Dell designs will provide the other 20%.

Fidelity has been moving away from Tier 1 suppliers to custom or "white box" suppliers such as ZT Systems, Avnet, Penguin, and Hyve, Brady says. The prices Fidelity pays for servers have declined 50% over the 2-1/2 years since the company started buying OCP-inspired systems from the custom builders, he says.

Goldman Sachs, like Fidelity, joined OCP when it was founded in April 2011, but it's not as far along in putting OCP systems into production. The co-head of Goldman Sachs's technology division, Don Duet, says he doubts that OCP, still in its toddlerhood, deserves much credit for reducing server prices at the firm, since hardware prices were already in a steep decline.

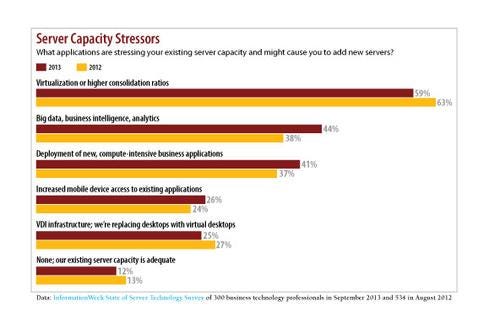

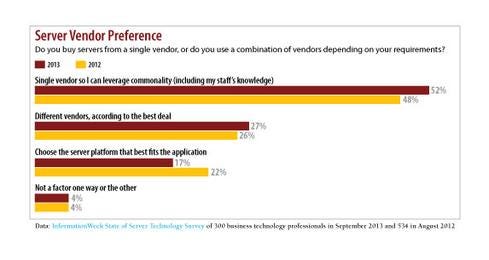

Figure 2:

The economics of open-source hardware are different from open-source software. A beginning programmer can download an open-source software program and make significant changes to it at no out-of-pocket cost. A beginning hardware architect can take an OCP design and ask a manufacturer to produce a different component, but it's going to cost that architect at least $400,000 upfront to retool a production line. Fewer than 10 manufacturers are building OCP-certified products today. So there's no guarantee that open-source hardware will follow the same path as software. But as corporate computing demands keep growing, open-source hardware will go somewhere.

It started at Facebook

The Open Compute Project began around designs for stripped-down motherboards for servers in Facebook's datacenter. It has expanded to designs for servers, racks, network switches, and even the design of the entire datacenter itself.

In one simple example, Facebook's IT hardware dispenses with the manufacturer's logo on the front of legacy servers -- the "vanity plates," as Facebook's Frank Frankovsky, VP of hardware design and supply chain operations and Open Compute's founder, puts it. Such adornments impede the airflow needed to cool redesigned server motherboards, and they only add cost.

Frankovsky's team is responsible for placing these servers in Facebook's massive datacenters in Oregon, North Carolina, and Lulea, Sweden. Other huge web companies such as Amazon and Google also design their own hardware, but they keep those designs secret, believing their engineering provides competitive advantage. Facebook's leap of faith is that by sharing its hardware designs, it can get more volume and new ideas behind those designs, and thus lower the overall cost of generating computing power to run its social network.

OCP backers have formed a well financed foundation and attracted a community of contributors around seven hardware projects. (See opencompute.org/projects.)

Participants in OCP include chipmakers Intel and AMD, which have produced designs for Decathlete and Roadrunner motherboards, respectively. Servers based on the motherboards are available from several manufacturers, including HP and Dell. Or a company can choose a design from among several OCP specs and hire a manufacturer to build custom servers based on it. That option is slowly giving rise to a new class of manufacturing from little-recognized manufacturers, threatening to disrupt the big three of HP, Dell, and IBM. The triumvirate commanded almost two-thirds of the x86 server market in third-quarter 2013, according to IDC. (IBM is in the midst of selling its x86 server business to Lenovo for $2.3 billion, precisely because it's low-margin.)

While the open-source hardware movement started around motherboards and servers, vendors of other types of equipment are taking notice.

In networking, the first designs for switches came in May, submitted by Broadcom Networking and Cumulus Networks, soon followed by Intel and Mellanox. Initially, the Open Compute Networking Project seeks to produce designs for top-of-rack switches, but it plans to expand into spine switches that connect rows of similar racks in a datacenter, potentially giving open-source switches a larger role inside the datacenter.

In storage, the Open Compute Storage Project includes Open Vault, which packs a set of 30 disk drives into a 2U rack space. The set can work with almost any host server, according to the OCP storage web page. This openness is a hallmark of open-source hardware; it's seeking to give users interchangeable parts, built by separate manufacturers to the same specification.

What do conventional vendors think? Dell, for one, doesn't think OCP will appeal anytime soon to IT managers outside of financial services. Dell is an OCP member, and it offers OCP-inspired Decathlete motherboards in its DCS 1240 servers. But all OCP designs have limited appeal because they spring from "a close-knit group in the financial services industry" and thus skew too heavily toward those companies' interests, says Stephen Rousset, director of architecture in Dell's datacenter solutions unit.

Something similar was once said about Linux and the Apache Web Server: They would be used only by developers and Internet startups. That software, however, is now mainstream in datacenters in every industry. So it's worth looking at why one financial services company, Fidelity, is so interested in the Open Compute Project.

One early adopter's experience

Fidelity is among the world's largest financial companies, with $1.88 trillion in assets under management. Brady, Fidelity's executive VP of IT, leads a team that's training employees "to bring different expectations " when they need computing power from the growing private-cloud datacenter environment. If developers in a business unit are creating a new application, they can provision servers themselves to meet the size and performance they need, knowing their unit will be billed accordingly. "When they're engaged in two-week app development sprints, they can get new capacity up and running very quickly," Brady says.

Instead of forcing the unwilling to use Fidelity's private cloud environment, Brady relies on volunteers. "There's been no top-down mandate to migrate," he says. Other groups have followed the lead of developers, and he describes "tremendous interest inside the company," with people creating and destroying thousands of virtual server instances themselves every month rather than waiting for IT to buy, set up, and deploy physical servers.

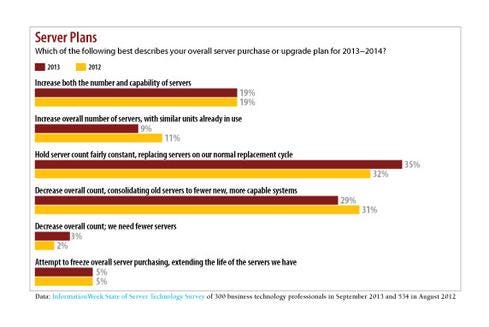

Figure 3:

"We teach them to fish, then we get out of the way," Brady says. "We think the culture has changed." A big change is that IT can say yes a lot more frequently, since it has more flexible capacity on demand when someone has a new idea that requires a new application and computing power. "We've lowered the bar to innovation. When someone wants to do something, we tell them to go do it."

Fidelity isn't looking to OCP only for hardware specs. It also wants to learn about a new style of datacenter operations, at massive scale, from one of the best teachers -- Facebook -- whose experience with rapid infrastructure build-out few can match.

Goldman Sachs is looking to OCP to reduce complexity as the firm's technology footprint grows, says Duet, who's also a member of the Open Compute Foundation board. "Simplification at scale is incredibly important to us," he says.

Threats and opportunities

OCP's participants reinforce the notion that the project is financial-industry-focused. When AMD announced its Roadrunner motherboard in May 2012, it explained that it was "specifically designed to meet the... compute and storage needs of the financial services industry." OCP's description of Intel's Decathlete board says it's a design for financial services.

Financial services firms have some needs similar to Facebook's around large server farms supporting a small number of operations conducted at very high volumes and speed -- make a trade, transfer funds, record a "like." OCP designs are optimized for such operations at a scale to which only a handful of companies will ever aspire.

One way to gauge the project's progress is to look at the list of OCP-certified product providers. It's short -- "under 10," says Facebook's Frankovsky. It includes Avnet, Quanta Computer, Penguin Computing, and Hyve Solutions, a unit of Synnex. Dell, IBM, HP, and Lenovo aren't on the list, which means they can't use the OCP trademark. HP and Dell are both members of OCP and produce what they say are servers that comply with OCP specs.

But the manufacturer validation process isn't firm enough yet for buyers to be sure what OCP-certified means, says John Gromala, senior director of product management for HP servers. "HP builds servers to the specifications set by our customers," Gromala says. "If they've ordered OCP-compliant servers, we've built them to the customer's satisfaction." In other words, HP isn't rebuilding its production lines to the interests of one narrow market segment.

Dell's Rousset predicts that upstart hardware vendors will have trouble meeting the needs of financial services companies, which tend to order hardware and expect delivery on short notice. For customers interested in OCP, Dell will supply them with servers based on a Decathlete-spec motherboard, though without the OCP trademark.

Cutting-edge engineering feats will likely continue to come from established hardware vendors. Consider one recent example, in which IBM redesigned solid state disk so that it can fit into the dual in-line memory module slots on a standard motherboard. IBM moved the fastest storage available inside the server case; that's proprietary engineering that only a few manufacturers are capable of undertaking. OCP is more about making the most cost-effective use of existing standard components, not doing expensive reengineering.

Intel, though a member of Open Compute, thinks companies will continue to pay for the sophisticated integration and testing done by HP, Dell, and Lenovo, whether they're building boxes with their brand names on them or not. "Vanity is often in the eyes of the beholder," warns Eric Hooper, director of cloud service optimization for OEMs and open design manufacturers at Intel.

In an interview with InformationWeek last fall, Cisco CEO John Chambers dismissed the white-box approach in networking -- where the hardware is dumb and controlled entirely by a software overlay -- as "fatally flawed." Most big companies look at the total cost of networking, including integration expense and technology upgrades over time.

"What customers are after is time-to-applications and future-proofing their environments, whereas the majority of the cost is combining vendors that weren't designed to work together," Chambers said. "And the only thing worse than vendors that weren't designed to work together are white boxes that weren't designed to work together."

Figure 4:

Brady says Fidelity doesn't expect or get the same level of support from white-box suppliers that it gets from HP or Dell. But then again, the white boxes are part of Fidelity's cloud operation, built on the premise that when a piece of hardware fails, the rest of the servers pick up the slack while the failed machine is replaced.

IT leaders at Fidelity and Goldman say OCP will help them get to a simpler, easier-to-manage environment. A standard management interface for a full rack of 42 servers, for example, would let them update or reconfigure those servers at the same time, rather than one after the other, as is usually done today. Simplified management in turn will exert a continuing influence over how future datacenter environments are built.

Will new vendors emerge?

Fidelity and Goldman are welcoming new x86 server suppliers, as open-source hardware creates new industry opportunities. Take Avnet Embedded, part of $26 billion-a-year electronics distributor Avnet Inc. Avnet Embedded was already an experienced hardware assembler and integrator when OCP published its motherboard spec in April 2011. But with those specs, Avnet could become a supplier of entire OCP-based servers. "You don't have to be as large as HP, IBM, or Dell. It's more like a cooperative," says DaWane Wanek, director of Avnet datacenter infrastructure and OCP solutions.

Avnet's 228,000-square-foot integration facility in Chandler, Ariz., houses an OCP Innovation Lab and produces OCP servers. The center also integrates and supports Cisco-NetApp FlexPods and HP Converged Infrastructure, and handles custom orders from system architects and independent software vendors. It ships about 475,000 systems a year. The company declined to say how many systems are based on OCP specifications, but it's a small fraction of the total. Avnet operates seven other assembly centers worldwide, including two in China, in Tianjin and Beijing.

In the past, custom server manufacturing involved orders for hundreds or a few thousand units. With OCP, there's the opportunity to follow a standard design and compete for sales to cloud computing and web service providers, online gaming companies, and search engine companies -- organizations that buy servers by the tens of thousands.

Facebook's Frankovsky says the major manufacturers may try to minimize the impact OCP already has had, but he warns that proprietary server-makers ignore open-source hardware at their peril. "This could be the best thing that has ever happened to them," he says, "or it could be the worst."

Frankovsky says he sees enough venture capital and startup interest in Open Compute to counter concerns that there won't be enough implementers of its designs. "All our members are real smart people," Frankovsky says. "I don't think they will sit and be caught on the wrong side of history." Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen was among the speakers at the foundation's Open Compute Summit in San Jose, Calif., Jan. 28 and 29. His firm, Andreessen Horowitz, has invested in Cumulus Networks (and Facebook).

While most of the Open Compute energy has been around servers and motherboards, Fidelity and Goldman are keen on storage and networking as well.

But critics point out that early adopters are companies with a few ultrahigh-capacity applications -- such as Facebook's social network -- and not the wide mix of variable-use applications common outside the web and financial industries. One project, Open Rack, was so specific to Facebook's datacenters that it couldn't be wheeled into any typical company's datacenter. The standard enterprise datacenter rack has 19-inch openings, and Facebook wanted wider openings to accommodate motherboards that had rearranged components for smooth airflow over the surface. The redesign prevented taller components from "shadowing" shorter ones, like CPU chips, lest the chips be deprived of their share of the cooling airflow.

Open Compute's potential beyond financial services is tied to the more general movement toward private cloud datacenters. Private cloud architectures like the one at Fidelity let users provision their own computing capacity as needed, so that the company can react more quickly to changing business conditions. Brady knew Fidelity couldn't get to a private cloud without learning new approaches from leaders such as Facebook. "If we had tried to tinker with the old datacenter, it wouldn't have worked," he says.

Duet at Goldman hasn't converted datacenters to OCP-based designs, but his staff has experimented with prototypes and is ready to adopt open-source hardware on a larger scale. "Management at scale is enormously important to us," Duet says. "We think 2014 will be a breakthrough year."

Read the whole Feb. 3, 2014, issue of InformationWeek.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like