Data can transform healthcare, but not with just any ordinary analytics.

Analytics -- the mathematical savior of oh-so-many population health management (PHM) programs -- is all the rage in health IT marketing circles these days. As the electronic medical records gold rush slowly ebbs over the next few years, attention is gradually shifting to approaches we can use to fundamentally change the cost and quality of care... and what we should do with all this data.

But how transformative are these PHM solutions? Many PHM offerings today look remarkably like yesterday's offerings:

Focusing on individual chronic diseases (as opposed to accounting more explicitly for heterogeneity and co-morbidities)

Relying heavily on claims data (despite the well-known limitations)

Lacking a larger inventory of factors with real predictive models

Including little-to-no near real-time interventional capabilities

For executives making decisions on new solutions, the issue is further clouded by marketing messages that describe any product capable of running a report as having "analytics" with "models" for improving the quality and/or cost of care. Is that really all it takes?

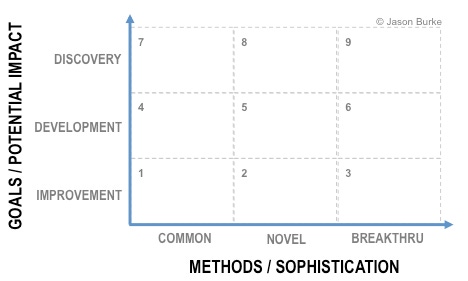

Along any organization's evolutionary journey, a disconnect can occur between an organization's goals and it's methods for attaining those goals. As the following figure illustrates, goals can vary from operational improvements to new discoveries in the practice, delivery, and reimbursement of care. Similarly, methods for achieving those goals can vary from current day-to-day techniques all the way out to breakthrough methods that have never been applied in healthcare. The disconnect comes when executives want to pursue more transformative goals, labeled "discovery" and "development" here, but only opt to use "common" methods.

Many PHM programs today include analytics that sit clearly in box 1 -- focusing on individual measures using descriptive statistics ("quality metrics" such as counts, averages, and percentages). Box 1 is good and important for many reasons, but can it power real transformation? For example, are yesterday's methods likely to surface and prioritize the current, real-world factors associated with variations in practice that impact efficacy, safety, and costs? Do they adequately capture the dynamics in population health delivery models? Or are they more likely to give us a lagging view of yesterday's beliefs of what might be important?

Health organizations need a balanced portfolio of health analytics capabilities -- some focused on supporting the status quo, and others helping the organization to pursue more strategic goals. If value-oriented transformation is a component of your organization's future growth, here are five questions that may help ensure you can get out of box 1 when needed:

How well does our data architecture provide reusable data assets that can be used for any clinical research or quality improvement projects? If the access, quality, and utility of data assets are primarily driven by questions already formulated (e.g., business intelligence and reporting), then it will be difficult to move beyond box 1 in our illustration above. If every project seems to include months of new data preparation work, which never gets used again by other project teams, a stronger approach to reusable data asset creation is needed.

How easily can we explore relationships BETWEEN different types of data (clinical, financial, administrative, patient-reported outcomes) as opposed to only within a single type of data? Many aspects of value-based care delivery are about balancing tradeoffs between costs, risks, and outcomes. If you only have partial access to one of those forces at a time, you cannot easily balance between them.

Are our methods tied to specific patient subpopulations, or are they extensible to any patient populations? Clinical practice often rightly focuses on specific patient subpopulations, but many of the analytical questions we seek to probe -- and the methods and factors we use to probe them -- are actually pretty consistent across populations. Flexibility, extensibility, and reusability should all be attributes of getting out of box 1.

What proportion of our analytical "models" are tuned to reflect the unique nature of our organization and it's patients? If you cannot iteratively refine the precision, accuracy, comprehensiveness, and utility of an analytical approach, then the approach is probably not delivering the best results.

Can our analytical models provide insight and action to any clinical, financial, and administrative systems we use, or are they closely linked to a single application? Analytics -- particularly analytics serving the needs of population health -- operate best when they a) have access to all of the clinical, financial, and administrative data possible, and b) are able to provide near real time insights back into provider and payer operating environments. Those two capabilities require fitting into enterprise architecture.

But these five questions are only a start. In moving towards true value-based care, the new leaders will evolve their data warehousing and health analytics strategies beyond the tempting thought that transactional/operational systems can easily provide analytics outside of box 1. The problem -- and opportunity -- in health transformation is much bigger than that.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like