If you have ever played a game against a computer, you played against an algorithm that used at least some math laid down -- or inspired -- by John Nash. Many of those same algorithms are being extended to cognitive computing outside of game situations.

Disney's Tomorrowland Past And Present: A Celebration

Disney's Tomorrowland Past And Present: A Celebration (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

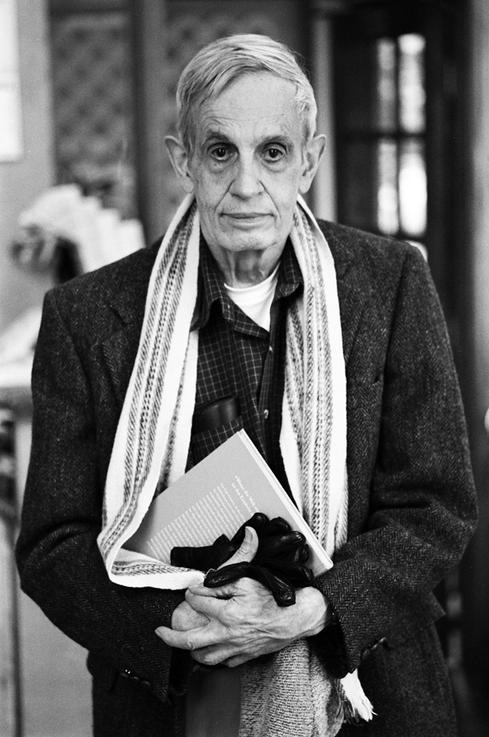

In an ending that is almost "too Hollywood" for such a long and storied career, John Nash, 86, died in an automobile accident returning to his home in New Jersey from Norway after receiving the Abel Prize, math's Nobel Prize. Nash, a diagnosed schizophrenic, was the inspiration for the film A Beautiful Mind. The crash also claimed the life of his wife, Alicia, 82.

There are hardly any computers in A Beautiful Mind. There's a good reason for that. Because of his mental illness, the entire first phase of Nash's career only lasted from 1950 to 1959. Nonetheless, as Nash battled schizophrenia, his work on game theory would spark revolutions in economics and artificial intelligence. It also won him a Nobel Prize in 1994.

[ Nash isn't the only math genius whose work has shaped IT. Read Pi Day: Celebrating the Math Gods Who Made IT Possible. ]

His work on Game Theory includes the eponymous Nash Equilibrium. It is a part of an essential piece of AI called the Minimax Algorithm. Essentially, what Nash did is explain how people behave in a non-zero sum game situation. Sometimes, in a game (or in economics) we try to minimize the maximum damage someone could inflict on us by preserving something for ourselves. That's minimax -- minimize the max. With the concept of minimax in mind, if you make a decision to act in a certain way because you believe I will act in a certain way, and I make the decision to act a given way because I believe you will act in a certain way, and neither of us changes our decision, we are at a Nash Equilibrium.

It sounds trivial, but until Nash pointed it out, and the math behind it, no one knew how to look at the way people made decisions in a mathematical way. It had a profound effect on economics. Until that point, it was assumed all rational actors were attempting to "win everything" or, at the very least, there was no mathematical model for not doing so.

The idea is illustrated, in a rather sexist way, in this scene from A Beautiful Mind. Ignore the 1940s attitude toward women, and you've got an understanding of the way people can make economic decisions.

If you have ever played a game against a computer, you played against an algorithm that used at least some math laid down -- or inspired -- by John Nash. Many of those same algorithms are being extended to cognitive computing outside of game situations. Central banks, insurance companies, and financial institutions all use computer projections which in one way or another likely use some Nash economics and math theories in their projections.

Essentially, what Nash did was quantify the rules behind the way decisions are made, whether by people or computers. Our modern economy runs partially on theories laid down 65 years ago by a beautiful mind indeed.

Nash's home page is still active on the Princeton Math Department website. Nash's files and notes from his current work are partially stored there. All these years later, after changing the world and battling an illness, Nash was still working on earth-changing subjects. He was working on the math to demonstrate when matter or fields are present that could generate "gravitation." Nothing like ending a brilliant career with a little cosmology.

I barely understood anything I read. But it was beautiful. There'd be notes like "we thought it would be easy to do [this incredibly hard thing most of us don't understand] but we ran into problems [we couldn't understand], but we're going to try [this other thing no one could understand]. There was a beautiful optimism and simplicity. He was talking about math only a few people in the world understand with the same attitude and clarity you and I would talk about going to the store. I guess, to him, it was just as easy.

My only regret is that someone who taught our machines how to make decisions didn't make the simple decision to wear a seat belt in a taxicab. Let's all buckle up and remember Nash's contributions to our industry.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like