A court has told Apple to compromise an iPhone owned by one of the shooters in the December San Bernardino attack that killed 14 people. But Apple should not be required to enlist in the war on bad things.

Encryption Debate: 8 Things CIOs Should Know

Encryption Debate: 8 Things CIOs Should Know (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

Apple has been ordered to work for the US government, without compensation, to undo the security system in one of its iPhones. The court order amounts to an endorsement of a surveillance state, not to mention forced labor.

The FBI won the order from a magistrate judge in Riverside, Calif. It directs Apple to create a custom version of iOS for an iPhone 5C that belonged to (but evidently was not managed by) the San Bernardino County Department of Public Health and was used by Syed Farook, one of the two shooters who killed 14 people in San Bernardino in December.

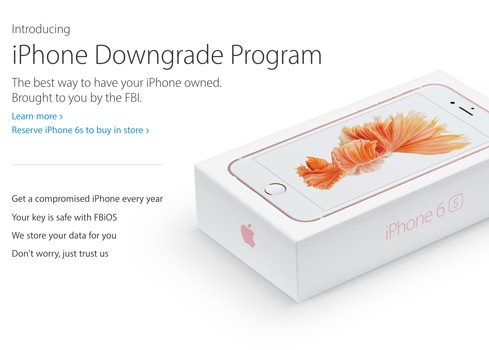

The custom software, dubbed "FBiOS" by security researcher Dan Guido, is intended to disable iPhone security features that delete phone data if the device passcode is entered incorrectly 10 times and that limit the number of passcode entry attempts that can be made per second.

Apple CEO Tim Cook said the company intends to challenge the order, stating that the "demand would undermine the very freedoms and liberty our government is meant to protect."

Nobody likes terrorists. But authoritarian coercion isn't the only alternative.

In this instance, the legal precedent matters more than the crime. If the case were different, if there were a nuclear bomb ticking away somewhere in a major city and the phone in question had information that could disarm it, any company that could help would do so. No judicial process would be required, even if it might be desirable as a matter of legal compliance.

That's not what's at stake here. This isn't a hypothetical scenario constructed to allow only one rational answer. The FBI may obtain useful information, but it may not. The agency doesn't know what's on the iPhone. Yet to access an unknown cache of data, the government has obtained approval for a judicial key that unlocks all digital locks.

The government suggests it only wants access to this one device. But Cook and others assert that granting the government's demand for access has broad implications. "If the government can use the All Writs Act to make it easier to unlock your iPhone, it would have the power to reach into anyone's device to capture their data," Cook said in an open letter to customers. "The government could extend this breach of privacy and demand that Apple build surveillance software to intercept your messages, access your health records or financial data, track your location, or even access your phone's microphone or camera without your knowledge."

Companies that do business in the US provide assistance to US law enforcement agencies quite often, either on a voluntary basis or in response to a lawful demand like a warrant or a National Security Letter. But the government hasn't publicly demanded that a business create custom software at its expense to undo the security it has implemented. Such malware might be expected from an intelligence agency, but not from a commercial vendor.

We've lived with technological insecurity for years, which is why encryption has never been a significant impediment to government investigations and intelligence gathering. A recent report from Harvard University's Berkman Center found concerns about encryption's impact on law enforcement overblown. There have always been enough vulnerabilities to exploit to deal with encryption.

But following Edward Snowden's revelations about the scope of government surveillance, things began to change. Apple and its peers began to realize that their businesses were at risk if they didn't improve the security of their software and hardware. Now the government wants to undo that work. And we need to re-examine the notion that any action taken in the name of national security should stand without question.

As the Internet of Things becomes more widespread, the government's ability to compel companies to grant access to any device means surveillance on demand.

[Read IoT Next Surveillance Frontier, Says US Spy Chief.]

It's bad enough that surveillance is a byproduct of connectivity. IoT alarm systems record comings and goings. Internet usage leaves tracks. Movement with a smartphone is easily mapped. Samsung has taken to including a warning in its privacy policy that its SmartTV may capture conversations in homes and transmit them to third parties.

Now imagine how the law enforcement agencies can magnify this IoT side effect if the FBI's demand for Apple's assistance is upheld. With easily obtained legal cover, authorities will be able to require that companies create custom software updates to reprogram routers, cameras, microphones, security systems, and connected cars, among other networked devices.

They may even be able to insist that these insecurity patches get pushed to individuals or groups silently, as over-the-air updates. And it's not just the US government that will do so. Every government of any significance will impose the same requirement, all in the name of protecting us from terrorism.

We can have protection if our data goes unprotected. That's the government's argument.

Developer Marco Arment offers a succinct assessment of the FBI's overreach: "They couldn't care less that they're weakening our encryption for others to break as well -- they consider that an acceptable casualty. They believe they own us, our property, and our data, all the time."

Tim Cook is taking an important stand. Steve Jobs would approve. As Jobs put it at the D3 Conference in 2010, "We take privacy extremely seriously."

Are you an IT Hero? Do you know someone who is? Submit your entry now for InformationWeek's IT Hero Award. Full details and a submission form can be found here.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like