Stakeholders from the war-torn country shared their stories of cybersecurity and data resilience at RSA Conference.

The persistence of the military and cyberattacks committed against Ukraine continue to put the country’s resilience in the spotlight, including at last week’s RSA Conference in San Francisco.

The digital aggression aimed at Ukraine is ostensibly tied to Russia’s ongoing invasive attempt to disrupt and seize full control of the country, a hostile campaign that began more than one year ago. Based on comments by speakers Dimitri Chichlo and Illia Vitiuk at the RSA Conference, cyberattacks against Ukraine occurred long before the latest military conflict -- and institutions under cyber siege in the country continue to learn and adapt their security measures.

Chichlo, vice-chairman of Ukreximbank, gave a presentation on “How Corporate Governance Transformed Cyber Resilience of a Ukrainian Bank,” where he shared his experiences being alerted to the onset of the invasion through the current efforts to keep the financial institution operating despite the ongoing aggression. Ukreximbank, a state-owned bank headquartered in Kyiv, is listed as systemically important, making its operation essential to Ukraine’s financial and economic systems.

Chichlo recalled first getting word of the invasion while on a plane from Warsaw headed for Kyiv, reading his Twitter feed. Thirty minutes into the flight that would have brought him to Ukraine, the plane had to turn back because the airspace was closed, he said. Soon after, he saw the first images of places in Kyiv he typically frequented that had been devastated by bombardment, scattering the populace. “Not everyone made it, unfortunately,” Chichlo said. “Crowds of people at the main train station evacuating city were leaving behind their sons, fathers, brothers, uncles.” Prior to the outbreak of the war, he said he divided his time between a home in Switzerland and Ukraine.

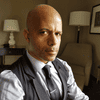

Dimitri Chichlo, vice-chairman of Ukreximbank, before speaking at RSA/Credit: João-Pierre S. Ruth

Chichlo gave a brief overview of the interconnectedness of banks with commerce and issues that led to the potential effects mistrust can have on banking systems. Russia’s previous annexation of the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine in 2014 saw disruption and devaluation of Ukraine’s currency. “A lot of banks fell into bankruptcy,” he said. That led to deep, heavy reform in Ukraine’s banking sector. “From 180 banks in 2014, now we have 67,” Chichlo said. Out of that 67, four banks are state-owned and collectively account for 43% of the banking sector in Ukraine, he said, posing a systemic risk for the country.

When rumblings of new aggression from Russia surfaced in 2021 with troop concentration at the border, Chichlo said, some early precautions were set in motion by the supervisory board that he belongs to. “We asked the bank to update, upgrade its business continuity plans,” he said. “One of the lessons learned is that for this kind of assessment, you have to also discuss with the military.”

The bank was also asked to engage in crisis management exercises, Chichlo said, but there were overestimations of how rapidly the situation would deteriorate.

Invasion Forced A Change in Data Policy

With the invasion underway, the bank had to adapt to a new normal and change its continuity plans. After evacuating employees and relocating the headquarters from Kyiv to Western Ukraine, teams were dispersed across different buildings in case of further bombardment. A digital relocation was also put in motion.

“We moved our data abroad,” Chichlo said. Until the invasion, Ukraine’s banks had not been allowed to house data abroad, he said, but national security called for such a change. “The risk of losing data was managed by moving data abroad,” he said, “but now our main issue is ensuring we’re able to get data. We ensure we have full internet connection redundancies to ensure we can get to the data.”

The migration of data abroad and into Microsoft 365 took two and a half months, Chichlo said. As the invasion advanced, including attacks on critical infrastructure such as electricity, the bank also sheltered employees in its offices with generators.

In the panel, “Stronger Together: The US-Ukrainian Cyber Partnership,” Illia Vitiuk, chief of the Department of Cyber and Information Security in the Security Service of Ukraine was joined on stage by Laura Galante, director of the Cyber Threat Intelligence Integration Center, and Alex Kobzanets, special agent with the FBI who was a legal attaché in Kyiv. Bryan Vorndran, assistant director with the FBI, moderated.

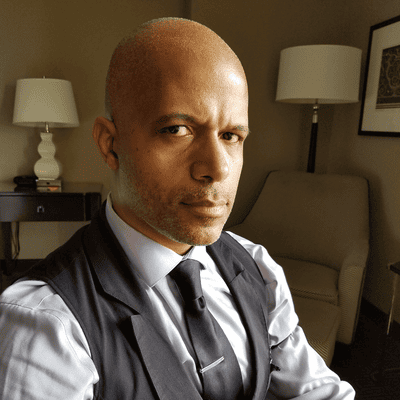

Alex Kobzanets, Illia Vitiuk, and Laura Galante at the RSA Conference/Credit: João-Pierre S. Ruth

The panel spoke on the FBI’s partnerships in fighting cyber threats, in particular with Ukraine. “The last year we’ve seen as a crystallizing event for how Russian cyber actors show their interest and capability around targeting critical infrastructure of the US and allies, of course in Ukraine as well,” said Galante. “That's included a focus on undersea cables and ICS [industrial control system] targets.”

Kobzanets offered the FBI’s perspective, noting that the agency maintains overseas offices that include dedicated resources to address cyber threats -- including in Ukraine. “Kind of a negative side of it is Ukraine is very impacted with cybercriminals,” he said. “A lot of FBI criminal investigations do have some connections to Ukraine.” This can include the infrastructure of cybercrimes being hosted in Ukraine or laundering of proceeds from illicit digital attacks, he said. “Ukraine is also home to some of our most dedicated and capable partners to combat cybercrime,” Kobzanets said, citing the Security Service of Ukraine and other entities.

A Continuing Tradition of State-Sponsored Cyber Attacks

Cyber intrusions into Ukraine began long before the latest invasion by Russia.

“We encountered Russian cyber aggression in 2014 when the war actually started,” Vitiuk said. “The number, and massiveness of the cyberattacks are constantly growing. Some of the attacks were notorious far beyond Ukraine.” He cited a 2015 cyberattack on Ukraine’s power grid, which took out the power for six hours, affecting 250,000 people. Vitiuk also pointed to the NotPetya ransomware attack of 2017, which affected more than 30 countries.

“You won’t surprise anyone in Ukraine with that now, but back then it was something extremely new and dangerous,” he said. “There are no types or combinations of cyberattacks we actually haven’t seen.”

Other types of attacks, including DDoS, wiper, supply chain, and man in the middle, have seen action in the ongoing aggression, Vitiuk said. “Ukraine has been for sure like a testing ground, firing ground for different types of Russian cyber weapons. Of course, we tempered and matured during this time.”

This has included changes to legislation and procedures, he said, as refining tools and techniques for cybersecurity. In 2020, Vitiuk said, the Security Service of Ukraine neutralized around 800 cyberattacks per year. By 2021, that was up to 1,400 cyberattacks. In 2022, when the full invasion was underway, that number increased to 4,500. There were also substantial cyberattacks attempted this year in January and February, he said. “We do believe that this was a test of our cybersecurity capabilities.”

Though about 70 state entities were attacked in January, Vitiuk said no significant damage was done. “We need new forms of how we can react quickly and jointly,” he said, saying different agencies must work on collaborating to avoid bureaucratic delays.

Bad actors linked to Russia have posed threats to other countries, Vitiuk said. “Today, as the war goes on, there is a number of them who call themselves hacktivists, but in fact, usually almost 100% of them are either state-sponsored or controlled by special services of Russian Federation.” He said hacker groups such as Killnet declare their intent to attack states that support Ukraine.

Despite the persistence of the attacks, Vitiuk maintains a positive outlook. “I believe that Ukraine digests most of the Russian aggressive cyber capabilities today,” he said.

What to Read Next:

What Ukraine's IT Industry Can Teach CIOs About Resilience

Ukraine Cybersecurity Message at BlackBerry Security Summit

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like