How To Tighten Data Security And Avoid A Major Trade-Secret Breach

A panel of data security veterans shared their recommendations on how to avoid trade-secret compromises.

Unless companies make some serious changes to their approaches for protecting confidential data, they're just waiting to be the next in line for a serious data breach. That was the message conveyed by a panel of data security veterans convened by Xerox in New York Tuesday to address threats -- both external and internal -- to trade secrets and other corporate data.

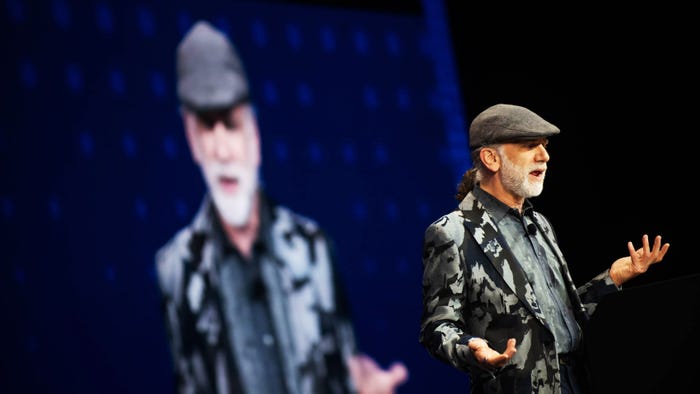

"There are catastrophic events awaiting companies" that are "structurally resistant" to believing that a given security threat pertains to them, John Nolan, a retired operational intelligence officer who in 1990 co-founded Phoenix Consulting Group, said Tuesday.

Indeed, trade secret compromises are inevitable if companies don't restrict access to a strict need-to-know basis and prohibit anyone but the highest company executives with access to the most sensitive data. "And have them sign contracts stating how they will use that information," R. Mark Halligan, a partner with the corporate law firm Lovells LLP, said during the panel discussion.

CEOs are less likely today to be frightened into making security investments than they were a few years ago. "It used to be that a CIO could walk into the CEO's office, pull out a headline about a security problem, and the CEO would get so scared that they would just throw money at a problem," said Dan Verton, VP and executive editor of Homeland Defense Journal and a former U.S. Marine Corps intelligence officer. "They've become so accustomed to this situation that they're not as worried about each individual incident."

Often, employees don't even realize that they have access to confidential information, so they don't take any precautions to protect that data. "It's not unusual for us to find scientists working for a pharmaceuticals company who are speaking with their peers and not following corporate disclosure guidelines," Nolan said. "They'll even discuss breakthrough work they're doing." Such loose lips could cause a pharma company to lose out on the benefits of being first to market with a new product, a mistake that would cost them millions of dollars. "Of course, the scientist isn't thinking about that," Nolan added.

Other employees unwittingly include trade-secret information when they post documents such as resumes online. "These are employees refer to confidential projects they're doing for the employer," Halligan said.

How did companies get here? At the root of the problem of confidential corporate information being stolen or leaked is a fundamental shift in what Nolan referred to as "the character of employees. Today, there's preoccupation with and assumption that employees can decide which rules they play by." Two decades ago, employees being told to comply their company's data disclosure rules would have responded with a simple, "Yes, sir," Nolan said. "There's a different employee mentality that's been shaped by the changes in our society." The implication is that any company that doesn't take into account that today's employees have a different perspective on corporate policy is in for a rude awakening when their corporate data ends up out on the Internet.

Verton made a similar observation, saying, "The workforce that you'll be hiring within the next five years has a vastly different understanding of what is acceptable use of computer assets."

Fortunately, there are very specific measures that companies can take to help them avoid being the next victim of a major data breach. One of the first things to do is figure out where you confidential data and trade secrets reside and who has access to this information. "Companies can tell you where every chair, every pencil is in the company, but they can't tell you where their key assets are--their information," Halligan said. "What I hear is that it's too overwhelming a task to track all of these critical assets. Everyone says they understand the importance of data security, but operationally they're not doing enough."

Another tactic should be to adopt a zero-tolerance policy for employees who want to use their work PCs for personal reasons, Halligan said. Anything less creates legal hoops that must be leaped through in order to confiscate an employee's PC. "If I want to take an employee's computer before they leave the company, I have to get a court order to do this if there is personal information on the computer," he said. "If there's no expectation of personal usage, then I can seize the computer immediately." This scenario is the most effective for keeping departing employees -- those who resign or are fired -- from removing any proprietary company information from their computers.

If all else fails, companies shouldn't rule out digging into their pockets to reward successful data security efforts. Sometimes, appealing to an IT pro's moral obligation to protect corporate data isn't enough, Halligan suggested, adding, "Some of this can be addressed through bonuses and incentives."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

How to Amplify DevOps with DevSecOps

May 22, 2024Generative AI: Use Cases and Risks in 2024

May 29, 2024Smart Service Management

June 4, 2024