Why Eli Lilly Might Talk To More Than One Cloud Vendor

In a discussion on cloud computing at the InformationWeek 500 Conference, Eli Lilly CIO Michael Heim disclosed that his firm has explored options with BlueLock and Savvis. Eli Lilly thus far has been strongly identified as a marquis user of Amazon's EC2. Could it be about to switch? Probably not but there's reason to shop around.

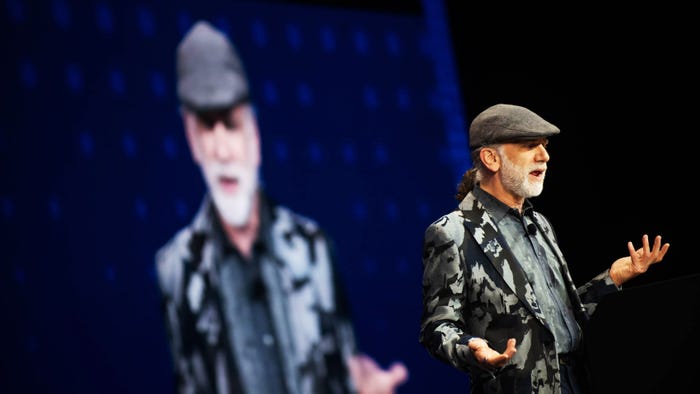

In a discussion on cloud computing at the InformationWeek 500 Conference, Eli Lilly CIO Michael Heim disclosed that his firm has explored options with BlueLock and Savvis. Eli Lilly thus far has been strongly identified as a marquis user of Amazon's EC2. Could it be about to switch? Probably not but there's reason to shop around.Heim's mention of alternative cloud vendors follows a reported discussion between Amazon and Eli Lilly on service level agreements. One of the less appreciated facets of infrastructure as a service, the form of cloud computing where all that's offered is a hardware platform on which to run a workload, is that service level agreements don't guarantee much at all.

You might think if you're paying for an hour's job on Amazon's EC2, and the hardware server dies, Amazon will make right your losses from the failed workload. But you would be wrong. Amazon's service level agreement provides the minimum. It guarantees 99.95% infrastructure availability over a year's period, which leaves an exposure of 4.4 hours of potential downtime a year. The SLA says in the event of downtime, the customer will get credits for the downtime hours they experience. At its most basic level, each hour of downtime requires Amazon to credit customers 8.5 - 12.5 cents per hour. There's no consideration given for the value of the job lost or loss to the business for interupted operations. It's strictly a matter of giving customers a like amount of credit for future EC2 hours to match the time lost.

Amazon has various recommendations and best practices that shift onto the customers the responsibility for seeing that their jobs are executed reliably. This can be done by duplicating data to different servers, so that a piece of hardware can fail but no data will be lost. It can be done by having a back up system on standby, preferably in a different data center zone than the one on which the job is running. In the event of a hardware failure, the job is transferred to the backup server and continues there.

That of course means renting two servers for jobs that require one, to the old way of thinking. But renting two to guarantee business continuity might not be such a bad deal.

I suspect Eli Lilly and Amazon Web Services unit have had some lively discussions on the fairness of these provisions of the Amazon SLA -- one is tempted to call it an unSLA. In the cloud, hardware fails and cloud software routes around the failure. Get used to it. Or get perhaps, get with it. Design your own workloads to operate that way, Amazon has basically told its customers since the EC2 became generally available in 2008. But Amazon is also being true to its mission of providing infrastructure only, with low rates and few guarantees. So far, there have been plenty of takers.

To be fair, Heim and his associate, Michael Meadows, made clear during their appearance at the Dana Point, Calif., conference that Eli Lilly thus far has restricted its use of the cloud and in no case is running sensitive clinical data or mission critical systems on EC2. It's main use is for scientific research and analysis of large data sets. The loss of a server hour here or there due to hardware failure is not going to have a serious impact on its business.

But the fact that Heim acknowledged an animated discussion with Amazon is telling. Rather say he was arguing with a supplier, he cited a locker room scene in the Tom Cruise movie, Jerry McGuire, where an athlete and an agent either argue violently or finally hear what each other is saying, depending on your point of view.

Heim and Meadows said they are exploring additional, longer term uses of cloud computing, which brings me back to their fleeting reference to Savvis and BlueLock. BlueLock is an infrastructure as a service provider, like Amazon, but it appears to take the vendor's responsibility for business continuity more seriously. In July, Gartner cited the shortcomings of cloud SLA's that resemble Amazon's, and BlueLock used the occasion to say it was trying to write SLA's in closer accord with the Gartner recommendations. Among other things, "technical limitations… are always discussed in the sales process" and a BlueLock SLA will address liabilities connected to an outage and provide remediation for business loss. I don't know exactly to what BlueLock does so. I merely note the willingness to accept responsibility, as opposed to shifting the responsibility to the user.

Likewise, Savvis is an even more extreme contrast to Amazon in that it comes out of the managed services and hosting world and takes responsibility for continuous operation and secure operation. Savvis operates 32 data centers around the world, 18 of them equipped to supply "private" cloud computing, according to an announcement in July.

It offers a choice of services and service level agreements, instead of one SLA fits all. It claims its Premier SLA guarantees both continuous operation and security for mission critical applications.

So there's a clear reason why Eli Lilly, a pioneer in cloud adoption, might be talking to suppliers in addition to Amazon. The early uses of the cloud have been experimental and non-mission critical, with software testing and research data analysis the leading examples. The next phase of the cloud will include operations that are critical to conducting business on the company Web site, scaling up transaction systems and maintaining customer relations.

Whether it's moving your email servers off premises or conducting crucial interactions with customers, the cloud will play both a cost saving and business continuity role in the future, and some providers will supply SLAs that match the importance of these business goals.

Amazon offers infrastructure as a service, and is trying to train its customers in the basics of cloud computing. Eli Lilly understands the basics and wants to move on to a form of cloud computing where the supplier guarantees high reliability in the operation of the underlying infrastructure.

The InformationWeek 500 Virtual Event gives you an opportunity to experience highlights from the live conference and exclusive content presented in a unique virtual environment that allows you to personally connect with C-level executives from leading global companies. It happens Sept. 29. Find out more.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

How to Amplify DevOps with DevSecOps

May 22, 2024Generative AI: Use Cases and Risks in 2024

May 29, 2024Smart Service Management

June 4, 2024