iPhone Encryption Battle: What Apple Can Learn From BlackBerry

BlackBerry was the preferred smartphone for business users a mere five years ago, until the company decided to allow certain governments to access user messages. Apple could face the same confidence loss from corporate customers if the company assists the FBI to crack the security of the iPhone.

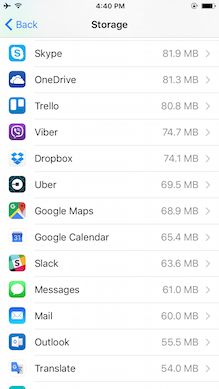

9 iPhone Hacks To Free Up Storage Space

9 iPhone Hacks To Free Up Storage Space (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

There is no shortage of news about the fight between Apple and the Justice Department to unlock the iPhone of a suspect in the San Bernardino, Calif., terrorist case.

Everyday we see some new development, new voices raising concerns, new issues, and new arguments in favor of one side or the other.

It's worth looking at recent history for insight into why Apple is fighting so hard to keep the iPhone secure, and why it is so vocal about its commitment to keep customer data on iPhones locked and safe.

Are you prepared for a new world of enterprise mobility? Attend the Wireless & Mobility Track at Interop Las Vegas, May 2-6. Register now!

Remember Research in Motion (RIM) in 2010? Back then, its BlackBerry smartphone was the king of corporate mobile devices. After a corporate restructuring, the company is now known as BlackBerry. But at the time, while RIM's consumer business was already suffering from competition with the iPhone and early Android devices, its market share in professional and corporate environments was strong. BlackBerry smartphones were secure and robust, and its mobile OS was considered the best operating system for enterprise and government use.

At that time, the BlackBerry Messenger (BBM) service was used worldwide as a secure form of communication; all messages were encrypted both on the phones and in transit. That made it basically impossible for governments and hackers to read users' communications unless they could access an unlocked device. Also, the RIM servers responsible for managing and delivering all the encrypted traffic generated by the millions of devices worldwide were located in Canada, effectively blocking any attempt by another country to access the data on its servers.

But some governments, especially in Asia and the Middle East, were extremely unhappy with the encrypted messaging service, and demanded full access to their citizens' messages on the BlackBerry Messenger platform. Initially RIM resisted, until those governments threatened to ban the BlackBerry service from their countries' cellular networks.

In August 2010, Saudi Arabia and RIM reached an agreement that enabled the company to avoid having its service banned. The deal involved the installation of a BlackBerry server inside the country, allowing the government to monitor users' messages. At the time, there were reportedly more than 750,000 BlackBerry users in the kingdom.

That same year, the UAE reversed its decision to ban BlackBerry service after reaching a similar deal with RIM. When asked about the deal, RIM stated that it "cannot discuss the details of confidential regulatory matters that occur in specific countries, but RIM confirms that it continues to approach lawful access matters internationally within the framework of core principles."

Faced with similar requests, and possible bans from other countries, including India and Indonesia, RIM said it did offer to help governments. However, it said, its technology did not allow it, or any third party, to read encrypted emails sent by corporate BlackBerry users. One of the arguments recently used by the US Justice Department against Apple's refusal to unlock the iPhone was that the company had made a "deliberate marketing decision to engineer its products so that the government cannot search them, even with a warrant."

RIM was initially able to avoid a ban of its services in India, one of its biggest markets, by providing the government with limited access to the lawful interception of data over the BlackBerry network. Then, in 2013 RIM reached a final agreement with India, effectively giving the country's intelligence agencies full access to the encrypted communications of private users. RIM tried to convince corporate users that their messages were still out of the government's reach, but no one believed them anymore.

I'm not saying that giving access to its users' communications was the main reason for BlackBerry's huge loss of market share, but it was an important factor. That is why Apple cannot be seen to cave to government pressure and break the security of its own products.

Even by hacking its own product, Apple will open the doors for others to try. In a recent op-ed in the Washington Post, Craig Federighi, senior VP of software engineering at Apple, wrote: "Once created, this software -- which law enforcement has conceded it wants to apply to many iPhones -- would become a weakness that hackers and criminals could use to wreak havoc on the privacy and personal safety of us all." He added: "When software is created for the wrong reason, it has a huge and growing capacity to harm millions of people."

Apple can, and should, comply with legal requests to deliver data it already has and assist law enforcement to obtain data on its products. But it should not be asked to create backdoors or special tools to break iPhone security. The reasons for that have been widely discussed in the media.

Interestingly, BlackBerry phones are not completely distrusted. The US government, for instance, uses them with additional encryption systems. These modified versions are considered reasonably secure, and are preferred over other alternatives by politicians, top executives, and, funny enough, even by law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

About the Author

You May Also Like