Neil deGrasse Tyson on Calling Out Bad Data and Appreciating AI

The host of the StarTalk podcast visited the Rev 4 conference and put an astrophysicist’s spin on data science and whether or not AI will destroy us.

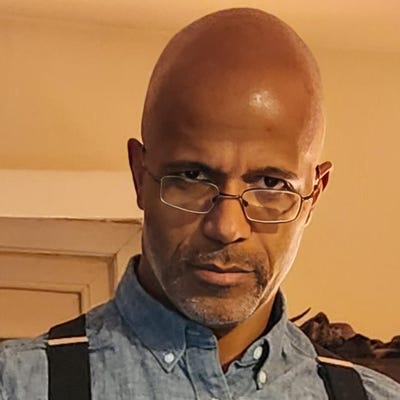

Noted astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson in a keynote last week talked up the importance of weeding out bad data and he also tried to bring calm to discussions about AI, while maintaining a need for oversight.

Tyson, director of the Hayden Planetarium and host of the StarTalk podcast, spoke at Rev 4 in New York, a data science and MLOps conference hosted by Domino Data Lab. The importance of data to science was central to his speech: “In my field, we’re data heavy. We have been at this for decades.”

Science, as a whole, matured after humanity transcended its five traditional physiological senses, Tyson said. Reliance on only taste, touch, hearing, sight, and smell as sensors to measure and understand the world could essentially be regarded as incomplete data. “The universe is under no obligation to make sense to us,” he said.

Tyson noted that even with resources to take measurements, some measurements are not precise while others are. “What are data if not the measurement of things?” he asked. Despite best efforts to take measurements and produce data, he said there are questions that in principle have no answers. “Measurements don’t produce exact information,” he said. “We just have to agree what the approximation is that we’ll accept upon making that measurement.”

The Necessity of Compute Power

Astrophysicists, physicists, the military, and a few other branches of society, Tyson said, were very early in the use of computers to assist their work as they become awash with data. The Gaia space observatory, for example, takes high-precision images of billions of stars in order to create a 3D map of the galaxy. “No human being can sit there and analyze all of that, so it’s all loaded up,” he said. “This is variants of AI that we’ve been engaged in for decades, where computers are making decisions for us once they’re trained to look for things that are interesting -- then they’ll find something that we might have missed, because they’re better at it.”

There can be flaws in the collection of data that emerge, however, even with advanced resources. Tyson said that time sampling needs to be handled properly to avoid becoming susceptible to artifacts. “If you don’t do it right, you can make things that move look like they’re moving backwards or not moving at all,” he said.

For example, a bird flying in front of a security camera might look like it is not flapping its wings because of the camera’s frame rate. “Your data aren’t always telling you reality,” Tyson said. With growing public concerns about racial or cultural bias in data, as well as the possibility of bias in the programmers behind the data, other issues can surface in data collection. “There’s also just data bias,” he said.

When Data Cannot Be Trusted

Personal observations may be significant in the judicial system, but they can be faulty when seen through a scientific lens. “There’s no such thing as eyewitness data,” Tyson said. “It is the lowest form of evidence in the court of science.” He cited a news story where visitors at an ice cream parlor claimed they saw him try several different flavors when he simply ordered his favorite flavor.

Reassessing observed data played roles in the discovery of celestial bodies in our solar system, Tyson said, such as Pluto -- which over time saw its status change from planet to dwarf planet. “The more we learned about Pluto, the smaller it got,” he said.

Data reassessments also ended the search for the mythical Planet X, which was supposedly affecting the orbit of Neptune. After discovering that bad data that had been relied upon from an observatory, astronomer E. Myles Standish eliminated it in the 1990s and other data sources were consulted. “Upon doing so, Neptune landed right on Newton’s laws,” Tyson said. “There was no need for a Planet X.”

AI is Already Part of the Equation

When asked for his perspective on AI, Tyson sought to cool some of the incendiary worries about its use and abuse. “The public now thinks of AI as an enemy of society without really understanding what role it’s already played in society,” he said.

Navigation apps are commonplace now and, as Tyson pointed out, are used with little uproar. “This is not a computer doing something rote,” he said. “It’s a computer figuring stuff out that a human being might have done and would have taken longer. No one’s calling that AI -- why not? It kind of is.”

The furor over AI caught fire after the technology saw wider use in nontechnical professions and communities, Tyson said. “What do you think it’s been doing for the rest of us for the past 60 years? When it beat us at chess, did you say, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s the end of the world?’ No, you didn’t. You were intrigued by this.”

He did suggest guidance should come into play with AI, but eschewed doomsaying over the technology. “AI, I don’t think is uniquely placed to end civilization relative to other powerful tools,” Tyson said, though he acknowledged the presence of fears associated with its unknowns. “We should fear it enough to monitor our actions closely.”

What to Read Next:

Tech Leaders Endorse AI 'Extinction' Bombshell Statement

Michio Kaku: Silicon Valley Will Become a Rust Belt in Quantum’s Wake

Lunar Data Center Concept a Giant Leap for IT

AI-Driven Satellite Connectivity Linking Up IoT, Edge Computing

About the Author

You May Also Like