Don’t Get Side-Tracked by Flashy Metrics, Success is in the People

Defining KPIs can be a whole different ballpark when you’re in public sector IT. But even if you’re not, the takeaway from these stories can easily be applied to the private sector: focus on the impact, the people, the customer, and success will follow.

“If you’d asked me 10 years ago if I’d work for government, I would have been polite and not laughed at you, but now I can’t stop [doing work like this],” said John O’Duinn, as he addressed a room full of government IT professionals at Interop ITX.

The reason for his civic-minded obsession? Better KPIs.

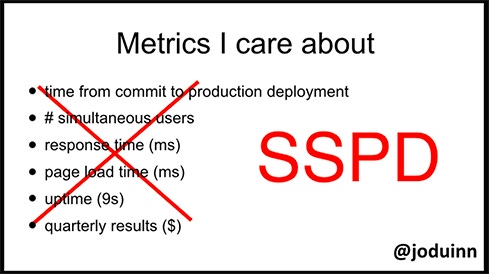

O’Duinn, currently a senior strategist for CivicActions, said that as an engineer he used to care about operational metrics such as response time, number of simultaneous users, and server uptime. After joining the United States Digital Service (USDS) under the Obama Administration and then CodeForAmerica, O’Duinn now passionately cares about one key metric: SSPD, or souls saved per day.

That core metric combines organizational goals with traditional systems operations metrics. “This focus guided [my] work at USDS, then at CodeForAmerica and now at CivicActions helping on the California Child Welfare System,” he said.

Here are two stories, outlined at Interop ITX and in published reports, that demonstrate the impact of thinking about tech in SSPDs.

How an update to a filing system has the potential to save lives:

As has been detailed in previous reports, the US Department of Veteran’s Affairs has had more than its share of poorly executed, pricey IT projects. At one point, the agency had over a thousand websites, according to reporting by Wired. An extremely generous person might describe their former benefits approvals system as clunky. At its worst, the department was so frustrating to engage with that people thought the government was purposefully short-changing them.

But the IT department at the VA wasn’t falling behind due to apathy, said O’Duinn, as he shared his telling of the state of the VA's tech woes to the room at Interop ITX. He saw employees on slim salaries thoughtfully and meticulously navigating mountains of paperwork (this is only a small exaggeration, they couldn’t exceed six feet tall) to help a stranger, driven by the care they had for a veteran in their community, or just because it was the right thing to do.

Scarred by false starts, it took some determined and passionate people to get the ball rolling on the floundering benefits processing system in the VA. The court of public opinion (and Congress) is not kind to government entities that don’t meet their goals. Stick your neck out, take a risk? No, not so much in government IT, and definitely not for a department that was already combatting a swarm of bad press. Can you blame them? Anyone with a Twitter account sweats a small drop before sending out a tweet in this day and age.

But proving something works is an amazing way to get someone’s attention, O’Duinn said.

A team of technologists with USDS took information that existed across the VA’s online entities and disjointed benefits processing system, built a more user-friendly website connected to internal back-end systems which streamlined the filing process for veteran healthcare, education, and a number of other benefits.

Instead of submitting paperwork to the VA (maybe twice, because the first time it got lost), said O'Duinn, or using a clunky -- there’s that word again -- website and hand-to-hand approvals system, veterans were able to submit materials online, through a website that was accessible on a smartphone (we’re talking a mobile-responsive government website) in order to receive the healthcare and other benefits they’d earned.

And it wasn’t a money pit.

The USDS team working on the Vets.gov project took $9.7 million worth of hardware and service maintenance costs and replaced it with $400,000 worth, “and it worked better,” said O’Duinn. To see a breakdown of the savings along with additional savings from the USDS VA project called CaseFlow, check out this Medium post.

Vets.gov has not replaced VA.gov or paper applications altogether, but it has worked to consolidate a good amount of resources and put redirects in place where those resources existed before (often times in many different locations).

“As more functions are built and enabled, more obsolete parts [that exist on VA.gov and elsewhere] get turned off and redirected,” said O’Duinn. While O’Duinn left USDS in January of 2017, the project is still alive and well, and resources are still regularly being redirected (to the arguably more streamlined) vets.gov.

While cutting down on the paperwork is a nice byproduct of vets.gov, the goal wasn’t to roll in with fancy technology and point to what they’d done, it was to get everything a US veteran would need to access and understand their benefits in one, easy-to-use place. And they’re on their way.

Screenshot of Vets.gov mobile website

For someone suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and trained to kill, being able to access healthcare in a timely manner can have a real life-saving impact, remarked O’Duinn.

Imagine solving infant mortality through better transportation:

The infant mortality rate (IMR) in Franklin County, Ohio, is one of highest in the nation, but by engaging with the members of their community most affected by this issue, Franklin County officials were able to isolate a significant factor in infant resilience. Here's that story:

By the end of 2015, the IMR in Franklin County had reached 7.6% -- that’s an average of two to three babies a week that never made it to their first birthday. In 2015, the average infant mortality rate in the US was 5.9%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The problem is so grave that the city of Columbus website hosts an online interactive infant mortality report presented through Tableau for Franklin County that allows the user to review infant mortality rates by month or year dating back to 2011.

Previous reports found that despite educational campaigns in Franklin County aimed at helping new moms understand pre- and post-natal care, infant mortality rates from prior years continued into 2016.

“[Franklin County was seeing] success with white moms and Hispanic moms, but with black moms of non-Hispanic descent, they were [really struggling],” said Beth Blauer, as she addressed the audience during her Interop ITX session, Creating a Path to Data-Driven Smart Cities. The executive director of the Johns Hopkins University Center for Government Excellence (GovEx) works to "improve people’s lives by bringing data into governments’ decision-making processes."

In 2016, Franklin County non-Hispanic black babies were 2.6 times more likely to die than non-Hispanic white infants.

Through analysis of their data, officials in Franklin County as well as partners assigned to the task force to lower the IMR, found that infant mortality campaigns were working best with mothers who had solid support systems, higher education, and convenient access to educational programs and hospitals. In a nutshell, they were biased in favor of white mothers and families.

Smart city programs such as the one in Franklin County are failing specific segments of their population, due to potential bias in that data, said Blauer, who worked on a case study of the efforts to reduce IMR in the county. “How can we [approach these initiatives] in a way that doesn’t exacerbate biases that have been built into the programs?” she asked the audience.

One way is to break your data into segments, rather than try to evaluate the data of a city or entity as one data pool, states GovEx's Roadmap for Policy Change, a guidebook for American cities working to address policy challenges in urban governance.

"Disaggregating data into more specific categories of race and ethnicity can help understand trends and disparities in a more granular way, which can help decision makers target policies and interventions in a more equitable way," stated the report.

Image: Shutterstock

To correct the racial disparity found in the infant mortality rate data, Franklin County officials and employees started talking to new moms that were having difficulties, either with feeding or not showing up for regular appointments. In targeted interviews, the mothers and families shared that they had no way of getting to the available resources, shared Blauer.

As new and expectant moms who already have a difficult time getting out of the house, reports found that the women in the most underserved areas had to take multiple buses, and sometimes a cab to the bus stop, all with a new baby in tow or pregnant belly, and frequently with other children who couldn't be left alone. All of this was often done without a robust support system to assist them.

“The public transportation system [in Franklin County] was failing mostly poor black women,” said Blauer at Interop, adding that their research showed that income and education were also significant factors in infant mortality rates “but the city controlled the way they deployed their public transportation ...and the transportation schedules, too," said Blauer.

Rather than try to rectify income and education inequality in Franklin County, Blauer told the audience that officials decided to place their focus on the one piece they had total control over, the transportation system. Multiple reports have found that transportation also significantly impacts the other issues plaguing infant mortality. If you build a more equitable transportation system, people are going to be able to get to better jobs and reach institutions of learning, and businesses will grow in areas with better transportation. Assuming these systems are built equitably, education and income increase for those communities.

So that's why Franklin County tackled the transportation system.

In June 2016, Columbus (seat of Franklin County) put in a bid for a $50 million grant through the Smart City Challenge that would enable them to overhaul their public transportation system -- from smart street lighting to smart electronic appointments and scheduling platforms. At the center of their argument was the impact a better, more equitable transportation system could have on the city's alarmingly high infant mortality rate. And they won the grant, beating out major tech cities including San Francisco, CA and Austin, TX.

After additional fundraising, the pot of money has grown to $500M with a goal of reaching $1B dollars to use toward these initiatives.

Columbus has faced some heat for dragging their feet on the implementation of these projects and pressure from programs like Moms2B and CelebrateOne -- two groups that are champions for the IMR cause -- to keep laser-focused on the issue at hand and not get distracted by the promise of flashy tech and urbanization. That being said, the city recently re-evaluated their proposal and made changes to the planned projects list, eliminating some projects they deemed would be ineffective or could be handled without the grant money, and included a project focused on the non-emergency medical transport for mothers.

Image: Columbus Ohio | Credit: Shutterstock

Through conversations on the ground with people in the most underserved segments of the population at the highest risk of infant mortality, Franklin County officials and employees were able asses the holes in their previous IMR strategy and secure a grant to help solve it. By taking a "second look" at their data, they discovered that a one-size fits all approach to a public health issue that affects several segments of their population was never going to succeed in bringing about positive change for all of those segments. They won the grant by presenting a vision of how technology can bring about significant social change, not because they wanted to implement smart technology to show the world what a cool city they are.

“This wasn’t about GPS monitoring, this was about routing and route optimization to meet the needs of an underserved population,” said Blauer. “[Smart city initiatives] cannot be just about technology and deploying tech.”

Essentially, look at the data and ask yourself, why your initiatives are serving some communities but not all. Then get out and ask those who have the greatest need where they're struggling, find the right tech for the solution. Not the other way around.

In order for smart city initiatives to work, you have to engage stakeholders, community members, frontline staff, the people who are thinking critically about the problems, said Blauer. If not, she says, you’ll end up with a mismatch of solution-to-problem, “like a hammer killing an ant or a dinosaur eating a breadcrumb,” and spend money on a project with no outcome.

And if your city or county has the kind of success in technology projects that result in lives saved or a major positive social impact, Blauer encourages officials to share those results.

“Don’t just create standards in your own city, share that plan with your [municipal] neighbors.”

[For more about IT in the government sector, check out these articles.]

How to Kickstart Digital Transformation: Government Edition

Interop ITX Reflections: Expert Advice, Predictions, and More

The Transformation of Detroit's IT: From Win XP to EMail that Works

Town of Cary Embraces the IoT to Serve Citizens

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

How to Amplify DevOps with DevSecOps

May 22, 2024Generative AI: Use Cases and Risks in 2024

May 29, 2024Smart Service Management

June 4, 2024