As companies push virtualization to more--and more essential--systems, things are getting complicated.

At Fair Isaac, the company that generates the FICO scores that decide many consumers' creditworthiness, virtualization has brought a lot of good--and some unexpected problems.

Fair Isaac has virtualized 70% of its servers, taking 5,000 boxes down to 1,500, reducing capital and power expenses. Furthermore, it used to employ one system administrator for every 30 to 50 servers; now it's one for every 150. "We'll be able to push that number as far as 250," says Tom Grahek, VP of IT. Fair Isaac has been able to run an average of 30 virtual machines per server and still consume only half of its available CPU cycles, Grahek says. His team can now provision a new Web server, database server, and application server in 30 minutes--"a process that used to be measured in weeks," he says--and decommission them just as fast.

Therein is part of the problem. That ease of provisioning has "created the perception that virtual servers are free," Grahek says. It used to be IT's decision whether to grant the request for server capacity, since those weeks of lead time provided a natural gatekeeper. Now Fair Isaac's IT team has put server templates in a catalog from which business unit end users can commission capacity themselves. The IT organization measures server use and charges that back to the business unit, so the line-of-business manager sees the cost and who's using the capacity.

"You're taking the power of IT and handing it over" to people in the best position to decide how to allocate it, Grahek says. Having overcome the "virtual servers are free" mentality, Grahek has a new goal for server virtualization: "We're pushing toward 100%."

Some 51% of companies have virtualized half or more of their workloads, our recent InformationWeek VMware vSphere 5 Survey of 410 business technology professionals finds. But that's also increasing the complexity--in how IT operates, but also in interactions with business managers, as Fair Isaac learned.

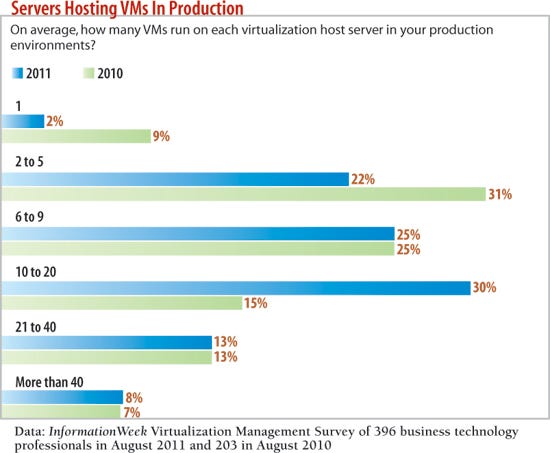

Virtualization keeps expanding: 63% of companies plan to have half or more of their servers virtualized by the end of 2012, according to InformationWeek's 2011 Virtualization Management Survey of 396 business technology pros. Production systems, once off limits, are now routinely virtualized to allow for more flexible management--to improve availability, load balance to meet peak demands, and provide easier disaster recovery. Virtualizing database systems is still rare, especially for transaction processing, but some shops are pushing ahead. "There's no technical reason not to," says Jay Corn, Accenture's North American lead for infrastructure and consolidation. "We have successfully virtualized Oracle database servers. There's never been data issues associated with it."

But as virtualization gets more intense, it ripples change throughout the data center. Virtual machines stacked 10 to 20 deep on a host server can generate a lot of I/O traffic. When those VMs include databases, the network has to accommodate many calls to disk, along with the normal SAN data storage and Ethernet communications traffic. That's uncovering what may be the data center's next big bottleneck. Whereas IT organizations used to be constrained by CPU cycles and even memory, now restraint has moved out to the edge of the server, to the I/O ports and nearby network devices.

"Heavily virtualized servers, still using legacy networks and storage, are choking on I/O," Corn says. That means 1-Gbps Ethernet switching is proving inadequate with the denser concentrations of virtual machines; time to upgrade to 10-Gbps devices. The network is lagging as a virtualized resource, and it likely will continue to lag until a new generation of switches materializes, possibly based on the OpenFlow protocol, that can treat the network as a pooled and configurable resource. (See informationweek.com/reports/openflow for more.)

Despite the complexity virtualization can cause, IT leaders can't afford a wait-and-see approach to expanding it. Yes, management software and standards are likely to improve, especially for cross-platform virtualization, which is a dicey move today (see "Private Clouds: Tough To Build With Today's Tech"). But IT teams are showing how they can push past technical and organizational problems now.

Diversity Breeds Complexity Our full report on virtualization management is free with registration.

Our full report on virtualization management is free with registration.

This report includes 41 pages of action-oriented analysis packed with 21 charts. What you'll find:

Data on virtualization use, from VMs per servers to what drives adoption

Data on plans for virtualization

Extreme Virtualization

Aaron Branham, director of information technology at Bluelock, an Indianapolis-based infrastructure-as-a-service provider that competes with the likes of Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, is ahead of most companies when it comes to maximizing server performance. Fifty-five percent of companies have six to 20 virtual machines running per host, our survey finds; Bluelock usually runs about 100 and has put 136 virtual machines on a four-socket, 48-core, 512-GB Hewlett-Packard DL 585 server. Branham says it's running fine.

Bluelock's business requires running many independent workloads at once, with unpredictable demand. In many virtualized architectures, one virtual machine trying to talk to another will send a message through the hypervisor switch and out to the network, even if the other VM is nearby on the same physical machine.

So Bluelock built its own architecture, working with HP and Xsigo, the supplier of Xsigo Director, a server dedicated to virtualizing I/O. Director has paired InfiniBand connections to move traffic off the host through the HP virtual switch, instead of the hypervisor's software switch, when traffic doesn't need to go out to the network, such as the database calls to disk, data storage traffic, and communications between VMs.

Such an architecture may be overkill for running five or six virtual machines per host, but about one-fifth of companies in our survey run 21 or more VMs per host. As they increase the number, they'll have to deal with this complexity of a constantly moving bottleneck in the data center. Intensively virtualized servers lead to heavier utilization of each related device, which the virtual administrator must keep in balance. Branham has cases where some aspect of the data center--the I/O, the network, the storage systems--has fallen behind, forcing him to find a way to bring it up to speed.

"We were choking in the old environment, with iSCSI storage causing all kinds of problems," he says. Now each server uses only two InfiniBand cables, plus a smaller, 100-Mb management network cable, as opposed to the former nine cables that tied network interface cards and host bus adapters to their storage and network switches. The bandwidth available per virtualized host has gone from 500 Mbps to 40 Gbps, and it's virtualized I/O that can be reconfigured as needed.

Branham does have a new worry: If a server were to falter, his CA Nimsoft monitoring system might warn of imminent component failure, but he'd still have to shift all those VMs to another server before disaster strikes. He can vacate (through VMware's vMotion) a 100-VM server in six to seven minutes--more like 10 minutes for the server with 136 virtual machines.

As companies work out these more advanced virtual architectures, Branham sees a skill rising in importance: accurate capacity planning. That skill hasn't been that important, as companies overprovisioned, placing availability over efficiency.

But the increasing use of metered systems, by both public cloud providers and in enterprise data centers, will make right-sizing resources to fit the task a requirement, not an option. "In the cloud, the incentive is to downsize and use only what you need," Branham says.

98% Virtualized

Capacity-planning skills will be in demand far beyond high-volume public cloud companies like Bluelock. As companies of all sizes virtualize production systems, peak demand can uncover new bottlenecks.

That was a worry for Raymond DeCrescente, CTO of Capital Region Orthopaedics, a division of the Albany Medical Center in New York. DeCrescente's team delivers practice management and back-office services to 32 physicians. They need their AllScripts practice management and AdvantX surgery center management systems, which include several SQL Server databases, available at all times. Soon the team will add electronic medical records to the list of essential software.

Just over a year ago, DeCrescente decided to reorganize his small IT shop around a highly virtualized data center, which would increase efficiency and let him establish a disaster recovery facility 20 miles away.He convinced the company's management and virtualized eight SQL Server systems and the practice management systems. They run on eight Cisco UCS blades and two regular rack-mount M200 servers, hosting 28 virtual servers; they'll eventually host 39. It cost $2 million to buy and implement, including the hardware, support, and VMware virtualization and disaster recovery software.

It's a big bill for the company, but with 96 GB of memory on each blade, and 12 Xeon 2.93-GHz cores, DeCrescente has so much spare capacity he doesn't anticipate more capital expenditures in the foreseeable future. His SQL Server databases are running without any detectable degradation, and all the interrelated parts--servers, networking, and storage--are easier to manage from the vCenter management console than they were as separate physical systems. That setup gives his staff time to establish the new disaster recovery center, test its failover capacity, and do other long-neglected projects.

Once DeCrescente phases out one practice management system that he kept with an Oracle database on its own server, he'll have virtualized 98% of Capital Region's environment. One fax server that won't work from inside a virtual machine will be the lone holdout.

DeCrescente faced skepticism--less from inside his company and more from software vendors that were wary of virtualizing production systems. "We had vendors very concerned about us going virtual as far as we have with their products," he says.

Virtualizing everything doesn't make sense for most companies. Dynamically matching resources to demand in the virtual data center remains a challenge, and it'll take increased cooperation between IT and business-line stakeholders to master that. It will also take data--probably a year's worth of IT operations data to know how much memory and other resources are needed for a virtual machine in different seasons, Accenture's Corn says. That data's often not available, and companies should consider assessing what information they should be collecting now to make the next wave of virtualization decisions.

All Articles In This Cover Story:

InformationWeek: Oct. 31, 2011 Issue

Download a free PDF of InformationWeek magazine

(registration required)

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like