GE CEO: IoT Boosts Safety, Efficiency, Speed

GE customers echo CEO Jeffrey Immelt's contention at Minds + Machines conference that Predix industrial analytics cloud is "about no unplanned downtime."

10 IT Infrastructure Skills You Should Master

10 IT Infrastructure Skills You Should Master (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

The Internet of Things is up and running for the ExxonMobil liquefied natural gas plant near Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea. The $19 billion project, with its myriad pipelines, valves, compressors, chillers, and equipment gauges that deal with extreme temperatures and pressures, presents an extreme challenge in operating reliably and efficiently.

The plant is located on the coast of Papua New Guinea, not far from gas production wells inland. Seven hundred kilometers of pipeline -- half running underground and half running underwater -- bring natural gas to the compression plant, where, in order to liquefy it, its volume is reduced to 1/600 of the space it formerly occupied. The liquefied natural gas must also be chilled to 160 degrees below zero to keep it a liquid in order to transport it around the world via supertankers.

Kary Saleeby, senior technical consultant for machinery at the ExxonMobil Production Company, told a crowd attending GE's Minds + Machines 2015 Conference in San Francisco Wednesday, Sept. 30, that ExxonMobil had GE's Predix analytics system "up and running when we started operating the plant." The plant made its first liquefied natural gas delivery in May 2014.

There were a few shakedown issues, but plant operators were soon skilled at reading the data summaries, charts, and highlighted anomalies captured by Predix as it gathered data from sensors and equipment around the sprawling plant, where 6.9 million tons of liquefied natural gas are produced per year.

[Want to learn more about GE Predix analytics? See GE: IoT Makes Power Plants $50M More Valuable.]

In the first few months, Saleeby said, gas detectors in a firing-engine enclosure signaled that they were detecting fumes when there were supposed to be none. All fittings, pipelines, and engine components went through a thorough check. "But we couldn't find a leak." A few years ago, that might have been the end of the attempt to address the problem, but knowledgeable operators went back and studied the data collected on the engines. They identified one component where pressure in its chamber was lower than that of others, and suspected something wrong with the dry seals around the component. The seals were well within their life expectancy. The operating crews hadn't expected a problem there, but a closer inspection found a tiny leak on one of them.

"It was at a braised joint, and you weren't able to see anything except when it was under pressure. We wouldn't have been able to find it if we hadn't known where to look," Saleeby told the crowd of about 700 in Fort Mason's Herbst Pavilion.

In another incident there was a problem with consistent operation of a valve actuator. By studying the data, operators could see that it operated normally when it was cold, but suffered power interruptions once it had warmed up. With the help of the data, the problem "was found and corrected," Saleeby said.

Neither issue represented a threat of catastrophic failure, but each small issue could have led to a piece of equipment being shut down and extensive maintenance routines undertaken, meaning a period of downtime for a section of the plant.

"The Industrial Internet is real. It's about more efficiency, more velocity, better safety … It's about no unplanned downtime," said Jeffrey Immelt, chairman and CEO in an address at GE's Minds + Machines on Tuesday, Sept. 29. "No unplanned downtime" became a kind of refrain at the conference as each speaker presented his vision of how collecting data off the Internet of Things was helping his company.

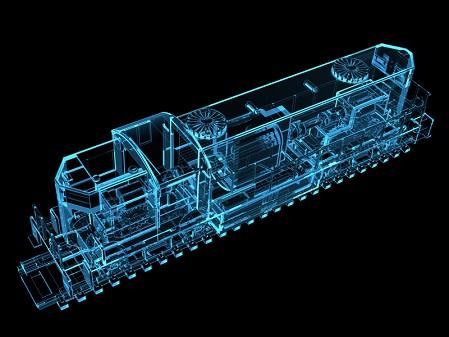

Immelt turned to one the favorite machines that GE produces, a railroad engine, and said: "We used to think of this as a locomotive. Now it's a rolling data center." The sensors on a locomotive are not just measuring the performance of its mechanical parts. They're also sensing the track beneath the train, since rails that reposition themselves often do so after bearing the extra weight of a locomotive.

That thought was carried out further by Sameh Fahmy, leader of executive sales in GE's Transportation unit. Fahmy has worked as an executive at several North American railroads. "When that call comes in at two o'clock in the morning, I knew what it was. I'd say, 'I hope it's not a big derailment.' Whatever it was, it was a disruption."

The railroad industry in the US loses about 300,000 hours a year in operating time due to derailments and other disruptions to the normal flow of traffic. These incidents are caused by many familiar problems: The bearings on a locomotive or car wheel have given out; a piece of track has buckled or is otherwise misaligned; a car wheel breaks.

It's not possible to inspect every mile of track manually before another train crosses it. Even when a railroad knows there's a track alignment problem building up, engineers often can isolate it only down to a 15-mile stretch of track. If it's viewed as an imminent hazard, then crews have to walk that 15-mile segment until the problem can be found. The disruption may last hours, Fahmy said.

More sensors on car wheels and more cameras on the locomotive gathering visual data on the track have been considered, but it's only when a network is available to move the data to cloud storage for processing that taking those steps starts to make sense.

That's what GE is proposing to do, starting early next year, as it establishes Equinix data centers and colocation sites as hosts of its Industrial Internet cloud and equips them with its Predix analytics. Predix is an analytics system produced by the GE Software unit. It's already been used by GE and a limited number of GE customers. It's being opened to a public beta this week, GE announced at Minds + Machines Wednesday.

Predix will become generally available sometime in 2016, said Hima Mukkamala, head of engineering at GE's Digital unit. "We want to use the beta program to learn more" about what customers need to know to put Predix to work on their own Internet of Things, Mukkamala said.

About the Author

You May Also Like