Hubble Finds Life-Sustaining Compounds On Planet

Detection of carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide could be evidence of life on the far-away planet, a NASA scientist said.

The Hubble Space Telescope has detected carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide in the atmosphere of a planet 63 light-years away.

The detection of organic compounds, which can be byproducts of life, could someday provide evidence of life on another planet.

The Jupiter-sized planet, called HD 189733b, orbits another star. It's believed to be too hot to support life, but NASA said the Hubble observations show that its instruments can measure the basic chemistry for life on planets that orbit other stars.

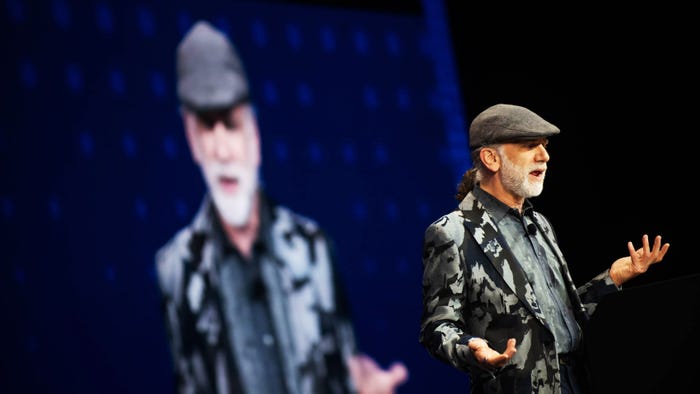

"Hubble was conceived primarily for observations of the distant universe, yet it is opening a new era of astrophysics and comparative planetary science," Eric Smith, Hubble Space Telescope program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, said in a statement released Tuesday. "These atmospheric studies will begin to determine the compositions and chemical processes operating on distant worlds orbiting other stars. The future for this newly opened frontier of science is extremely promising as we expect to discover many more molecules in exoplanet atmospheres."

NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory Research Scientist Mark Swain studied infrared light that the planet emitted. Gases absorb different wavelengths of light, and the Hubble's infrared camera and multiobject spectrometer allowed Swain to spot carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide. NASA said the discovery marked the first time a near-infrared emission spectrum has been obtained for an exoplanet, a planet that orbits a star other than the sun.

The Hubble and the Spitzer Space Telescope had already detected water vapor on HD 189733b, and, earlier this year, Hubble discovered methane in HD 189733b's atmosphere.

"The carbon dioxide is the main reason for the excitement because, under the right circumstances, it could have a connection to biological activity as it does on Earth," Swain said. "The very fact we are able to detect it and estimate its abundance is significant for the long-term effort of characterizing planets to find out what they are made of and if they could be a possible host for life."

NASA was able to isolate emissions from the planet during an eclipse, which occurs nearly every two days when HD 189733b passes behind the star it orbits.

"In this way, we are using the eclipse of the planet behind the star to probe the planet's day side, which contains the hottest portions of its atmosphere," Guatam Vasisht, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said. "We are starting to find the molecules and to figure out how many there are to see the changes between the day side and the night side."

The findings provide hope for observing biomarkers on a planet the size of Earth or larger after NASA launches its James Webb Space Telescope in 2013.

"The Webb telescope should be able to make much more sensitive measurements of these primary and secondary eclipse events," Swain said.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

How to Amplify DevOps with DevSecOps

May 22, 2024Generative AI: Use Cases and Risks in 2024

May 29, 2024Smart Service Management

June 4, 2024