NASA Explores New World Of Open Data

NASA has been publishing a lot of data for a long time, but getting it into standard machine-readable formats is still a herculean task.

NASA Spinoffs: 6 Innovations In Health & Medicine

NASA Spinoffs: 6 Innovations In Health & Medicine (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

NASA has been an open data operation since the passage of the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958, in the very earliest days of the Space Race after Sputnik. The agency has always published untold volumes of scientific data.

Yet the kind of standardized, machine-readable data demanded by the Obama Administration's Open Government Initiative remains a challenge.

"That made more complicated -- or, you might say, made wonderful -- the job we were already doing," NASA open innovation program manager Beth Beck said in an interview. "Big data is NASA -- that's what we have -- but taking all that data and making it machine readable, that's a big job." Most of the data is already digital and readable by some internal applications created by NASA and its network of contractors. The challenge is finding it in a sprawling, decentralized organization and putting it in a form that others can use. Some important data is locked up in the form of PDFs of scientific articles, when a data analyst would much prefer structured XML or even a comma-delimited download of tabular data.

[Seeking truth? Truthy Project Not Orwellian, IT Groups Tell Congress.]

That job rests on Jason Duley, whom Beck introduces as her "data emperor." His real title is lead software developer for the open innovation team. NASA has established the data.nasa.gov website, which feeds into the centralized data.gov catalogue established by the White House. NASA's open data effort has intensified since February or March, when the White House Office of Management and Budget began pushing the open government policy harder, Duley said. A year ago, NASA had 25 published open-data sets. Within a few months, Duley expects to have more than 4,000 available. However, that is still only scratching the service.

"The biggest challenge is finding the data, because NASA is so large, and the field centers all operate like different corporations, and they all have a different governance model," Duley said. There is no guarantee that important data even resides on a NASA server -- sometimes data storage is delegated to a contractor, and there might be no way of knowing that if you weren't part of the project that created it.

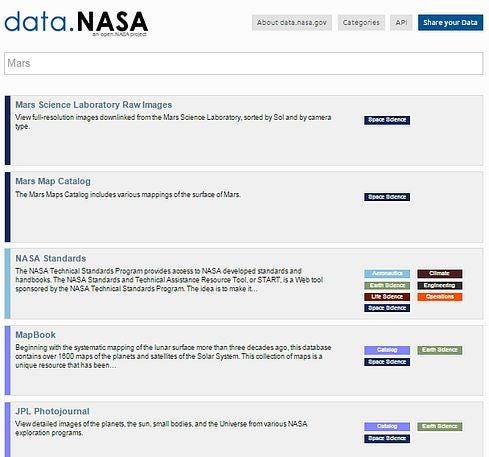

Figure 1:  Mars data from data.nasa.gov.

Mars data from data.nasa.gov.

"There's not a clear process where someone initiates a workflow to open their data," Duley said. Beginning to create that workflow and a standardized information architecture is one of his current goals. "There should be a notification scheme that will allow us to discover this data, rather than have to hunt for it. I want to delegate responsibility for modeling the data to the people who own it."

The process has to be efficient, Beck said, because the open data initiative is essentially an unfunded mandate, or at least there is very little additional money available to make it work. "It's not our mission to be the data-on-demand agency, but that's one of the mandates. It is dizzying, very hard to keep up with what new mandates are. Even if we put a process in place, the mandates could change."

In particular, the OMB is now asking NASA to identify the top five users of its data from outside government and how they are using that data -- something the agency has never tracked before, or not in a systematic way. The agency is supposed to be able to show "what are they using the data for, what's the financial benefit they get from it, and why do they want the data," she said.

Duley said one possibility for tracking usage more accurately might be to make data available through an application programming interface, rather than straight data downloads. "That would give us traceability into who is using our data, to what extent, and what services they're accessing."

API access to NASA data might also be a way of bringing open data and big data together more, allowing outsiders to access and manipulate the data without necessarily downloading it in bulk. Almost by definition, true big data sets are too large to download easily.

Though Beck's group is working to set up a repository for scientific publications, in most cases it will not host the data itself. Instead,

the goal is to provide a catalogue of data sources with pointers to websites where they can be accessed.

"Knowing that we have exabytes and petabytes coming down from satellites, to me we haven't even scratched the surface," Beck said. Given the necessity of setting priorities, she and Duley have focused on reaching out to the parts of the agency most capable of coming up to speed quickly. Luckily, several NASA programs, particularly those related to Earth sciences and climate research, are more mature in their approach to publishing data. That's because they have long-established relationships with external corporate and academic consumers of that data.

"If you look at climate data, we've been working on that forever," Beck said.

More obscure data sets have an audience of their own. Duley uses the example of a website he managed on research about outgassing -- how much different paints and casings and other substances slowly evaporate when exposed to the vacuum and temperatures of space. That is specialized knowledge, but if you're designing a satellite or a space exploration robot, it's compelling reading -- and when the site went offline for maintenance, Duley got a half-dozen emails every day asking when it would be back.

Telemetry feeds from the International Space Station are an example of data that is readily available but not necessarily easily understandable, Duley said. "They're really not documented very well, so you'd have to go to a website and reverse-engineer how to connect with it." One of his goals is to do a better job of putting such data sets in context.

One of the best open data success stories to date concerns Dan Hammer, whose Global Forest Watch project recently won the UN Big Data Climate Challenge. Prior to joining NASA as a Presidential Fellow, Hammer had already tapped into NASA data on behalf of a United Nations program to monitor deforestation. He led the development of analytic software that made use of data from NASA's Earth-watching satellites. "It had nothing to do with NASA, except that it was our data," Beck said. At the time, Hammer was working for an independent research organization, the World Resources Institute.

That's exactly what open data is supposed to accomplish, Beck said. "This is a way to get more innovations from our data than we would have imagined, just because we don't have time to think about it."

She is also proud of the NASA Space Apps Challenge, where anyone can compete to do something cool related to NASA data or problems in space science. The "people's choice" winner in that competition this year was a space helmet smartphone. Another winner, SkyWatch, provides a visual representation of data collected from observatories around the world in near real-time.

Regardless of concerns about mandates from above, Beck said, "We want to make our data public, period. There's just a new way of making it public."

Enterprise social network success starts and ends with integration. Here's how to finally make collaboration click. Get the new Enterprise Social Network Success issue of InformationWeek Tech Digest today (free registration required).

About the Author

You May Also Like