Project Management Gets Lean

IT can't afford to do projects the old way. Lean project management gives a better picture of success or failure.

Technology projects can make or break a business, which makes IT project management a big deal. Unfortunately, the pressure for such projects to succeed may be blinding IT and business leaders to the benefits of failure. The emerging concept of lean principles in project management encourages the idea of failing fast--that is, before large investments are made.

The general idea behind a lean enterprise is efficient application of resources and continuous improvement. A real-world example is Toyota's just-in-time manufacturing approach. Eric Ries' book The Lean Startup popularized lean with young companies, but terms such as "minimum viable product" have made their way into the general business lexicon, and lean startup lessons about batch sizes, metrics, and continual learning are starting to influence mainstream project management teams and the business leaders who work with them.

The lean approach focuses on the entire outcome of a project and whether you should even be doing that project, in addition to the traditional project management focus on controlling activities. Much like agile development principles, lean startup principles measure ongoing results but then challenge those requirements as needed, as part of a build-measure-learn loop. A true picture of success or failure starts to emerge--and a true picture of failure may induce even the most intractable project sponsors to make significant changes before things go off the rails.

For example, usage numbers are frequently trotted out to show that all has gone well with a system project. "They're using the system; they must love it," the thinking goes. This metric will go up and to the right as the system becomes more entrenched. But that's a "vanity metric," because most any system, as it becomes entrenched, will add users and usage.

A better metric is one that answers the question, Is this project fixing the problem or creating the business result that it was intended to? For example, are repeat customers coming as a result of the configuration of the new CRM system? That is, after all, why business leaders funded the project. This is a metric outside of IT's control, but it's the one that matters. A metric like this one can be used for early intervention. It's a way of telling that the project isn't succeeding even if all milestones have been met. A metric like this one can help you either modify your approach to an ineffective project or cancel it--either way, the company benefits.

One warning: Lean requires learning and the ability to say, "Yes, we're failing." It probably won't help organizations whose cultures let managers protect their egos.

Research: 2012 Enterprise Project Management

Our full report on enterprise project management is free with registration.

Our full report on enterprise project management is free with registration.

This report includes 28 pages of action-oriented analysis, packed with 22 charts. What you'll find:

Principles of lean project management

Survey results from more than 500 IT professionals

Fear Of Failure

A major roadblock to project management learning is the reluctance to look at previous failed projects, says Donald Jessop, a team lead for the Alberta educational system. "The idea that a project 'failed' or was not successful is tantamount to a slap in the face" to some project managers, Jessop says.

Bottom line: Cultures that discourage talking about failure will still be cultures that discourage talking about failure, lean or no lean. But cultures that encourage risk taking understand that not all efforts are successful, and they emphasize that mistakes are the only way to learn.

Lean challenges us to think hard about all the metrics we've traditionally used.

On time? What does that really mean? Usually there are three basic constraints to a project: scope, schedule, and budget.

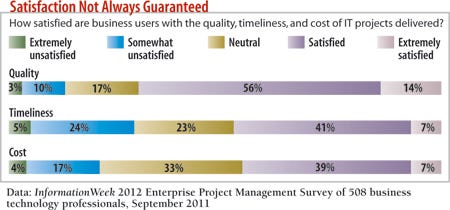

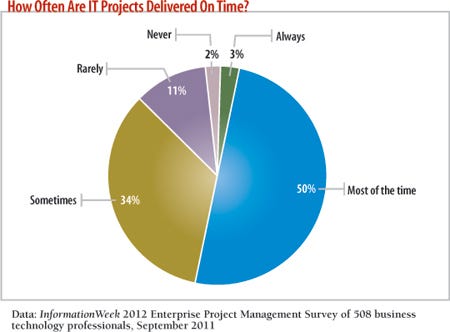

While 53% of the 508 business technology professionals who responded to our 2012 Enterprise Project Management survey say their projects are "on time" all or most of the time, we now wonder whether the better question might have been, "Do your projects typically meet all constraints of scope, schedule, and budget?"

But again, this may be more of a vanity metric than anything else. In reality, IT projects that need shooting must be shot without mercy or remorse.

Likewise, give more time to projects that, after due deliberation with business stakeholders, are determined to be worthy of more time. And projects that would deliver more value through more investment should get it.

We need to be measuring the doughnut, not the hole.

While you might think that our survey respondents overstate their customers' satisfaction, consider that 70% of their customers are said to be satisfied or extremely satisfied with project quality, while only 48% are said to be satisfied or extremely satisfied with timeliness and only 46% are said to be satisfied or extremely satisfied with project costs. Those are failing grades by most standards.

The Big Change

When projects don't work out, there's plenty of blame to go around. Our survey respondents cited everything from a lack of business engagement to a failure of executive IT leadership. A lack of support, training, documented requirements, and sponsor involvement all made it into the 7% of "other" responses that we received on why an IT project might not have delivered expected results.

Sometimes, the PMO and its project managers are considered the problem.

Thomas Stanley, VP of infrastructure operations at LexisNexis, questions the value of formalized programs and formally trained project managers. "Things get done in spite of the certified project managers," Stanley says.

Wow. But he's far from alone.

Again, our data suggests that satisfaction with the project management process is pretty low. Just 30% of respondents say IT projects almost always deliver value to the business. If you had an employee who didn't deliver value most of the time, you'd put him or her on probation.

While most project management offices (PMOs) understand what they're doing, the same isn't always true for the business folks who interact with them. Project managers can get so wrapped up in Gantt charts, time sheets, and forecasting that they don't always take the time to explain what they're doing. Folks can feel like projects are happening to them instead of feeling like they're participating in a worthy cause.

Get Traction

This, friends, is the reason customers feel as if project management isn't helping them. Maybe the solution is more and more status meetings, but we doubt it. Look at it this way: You're moving cheese every time you embark on a significant business technology project. You're changing the way people do their jobs. But if IT is inflicting the project on other parts of the business, if business units aren't all "hurry up and get it done--this is awesome," you're doing it all wrong.

Alex Adamopoulos, CEO of project portfolio management consulting firm Emergn, tells the story of a large logistics client. "There is no longer such a thing as 'the business' and 'IT,'" Adamopoulos says. "It's one organism."

The logistics company had decided that the various bureaucratic gateways and checkpoints of conventional project management were slowing it down. So it blended responsibilities for business technology projects with the idea that it could either execute quickly or quickly decide to kill the project if it wasn't well conceived--before it's so far down the life cycle that the money has been spent. Adamopoulos says the company has saved millions by failing fast.

His challenge to PMOs: "Pick a project type that you're struggling with. Run it through the lean model, and compare the results. It will be dramatic."

Now for the elephant in the room. We think it's time for PMOs to start admitting that while projects are about executing tasks, managing risks, monitoring budgets, and updating statuses, that list should also include managing organizational change. Much has been written about why projects fail, but the underlying cause can, in many cases, be simplified to a resistance to change.

The official-sounding moniker "organizational change" boils down to "how people feel," which will send many technical and process-oriented staffers fleeing from the room, or at least snickering when nobody's around.

Mary Lynn Manns, author of Fearless Change, a prescriptive handbook on organizational change, says that people who are behind business process change tend to document business processes very well. They think their well-researched and well-written documents will be the magic bullet that will get change done.

Nope.

Any process change is about folks letting go of the old ways, Manns says. Unfortunately, champions of process change often fail to realize that there's a reason people are tied to the old way of doing things: They do it every day. There's a personal connection and investment.

Letting go can create something very much like a grieving process: anger, disorientation, confusion, sadness, even a little depression, because people are no longer as good at their jobs as they used to be.

A standard project process includes business leaders at every step, identifies why the project is needed by the company, sets clear goals, and initiates controlling processes for budget and tasks. That's all good, but it's not enough.

For the project to truly get traction with the constituents who matter--the people who will be changing their way of doing things--all those goopy feelings have to be taken into account. Saying, "This is what's good for the organization" without also saying what's good for the people doesn't convince people to change, Manns says.

Compliance Vs. Participation

It's tempting for process-oriented individuals to think that if they just had the right tools--maybe the latest and greatest PPM suite--people would start falling in line. Not so. Consultant Adamopoulos pithily notes that tools don't follow processes that people don't follow.

So how do you get them to comply? The short answer is, when they're not sold on a project, people will still comply for one of two reasons: because they want to keep their jobs or because they don't have the energy to fight.

But when you continually compel smart people to comply, expect occasional ambushes and passive-aggressive behavior, Manns says. The silly stuff that can ultimately lead to failure.

So instead of compliance, think "participation." Compliance makes everyone feel like a prisoner, constantly thinking of ways to escape. But participation--where individuals are part of the process, where they really have a voice--makes everyone feel like they're part of the solution. It's not being done to them; they have all created their future together.

One strategy we've seen over the years is to involve all levels of staff in the original decision-making process. Much like a worker in a Toyota factory is empowered to pull the lever to stop production, a fully involved participant in a business project should be fully empowered to raise the flag when something doesn't make sense--and he must know he will be taken seriously.

Even when you get solid change management, business direction, and project management principles in the room, it's hard to sustain the direction. Matt Anderson, director of program management at Cerner, which makes and sells software and services to healthcare providers, makes the point that once folks adopt a new set of principles or practices such as agile, they want to declare done and then focus their attention somewhere else.

Tool Or Straitjacket?

Project management tools are hard to select and work with, they're not one size fits all, and when you find one that does one thing well, it seems to do other things poorly. Simple project management tools like Basecamp don't have the killer feature of timesheets. But to be fair, they also don't require users to spend five workdays learning their ins and outs.

Which project management tool should your company adopt? It depends on what you want. If task management and collaboration are important, new tools such as Flow may be what you need. If budget management is important, consider either a full-featured project management tool like Clarizen or, hell, just throw numbers into a spreadsheet if it's a simple project.

Bottom-up innovations don't come from 11,000 or even 1,100 employees moving in the same direction at the same time. They come from small groups of employees who are free to choose an appropriate tool set to execute on their vision. We're not saying there's no use for big project management packages like Microsoft Project or Métier's WorkLenz, but don't fool yourself into thinking that such packages will be the only source of project data or that the gigantic backhoe is the only effective tool that your little farm can use. The reality, according to our research, is that a variety of tools will yield the best outcomes.

Letting project managers pick and choose their tools goes against the common wisdom of having a standardized enterprise architecture.

But this, too, is an illusion. As long as there are people who individually contribute to a project, there will be different ways of tracking progress. If IT thinks that the way it imparts value is to put a straitjacket on these individual contributors, IT has failed.

"The complexity of project management tools only adds to the confusion of IT efforts," says Jeff Hasenau, a manager for T-Systems, Deutsche Telekom's systems integration and networks services business.

To which we'd counter, if you offer a tool at the right complexity level for the project or workgroup, you have taken a frustrated customer and created success.

The key, as with any enterprise system, is to hide complexity when you can. Ease of use leads to adoption.

If complexity is needed for a rich set of features, think seriously about the audience. Do all end users really need to log in to the big, honking system, or would it be OK for many to use something simpler?

By all means, project managers need power tools, and but avoid painting every employee with the same brush, and think before you inflict a complex domain-expert tool on someone who's not a domain expert and just wants to do his or her job.

The nature of business technology improvement projects means that you're never done. Continuous improvement means continuous attention to projects and sufficient resources to carry them through. It also means having the ability to fail fast and the ability to learn from that failure.

Jonathan Feldman is director of IT for a city in North Carolina. Write to us at [email protected]

InformationWeek: Feb. 13, 2012 Issue

Download a free PDF of InformationWeek magazine

(registration required)

About the Author

You May Also Like