Who Owns EHR Data?

The owners of electronic health records aren't necessarily the patients. How much control should patients have?

Download the entire September InformationWeek Healthcare, distributed in an all-digital format.

Download the entire September InformationWeek Healthcare, distributed in an all-digital format.

Electronic medical records contain highly personal information, from illnesses to family matters to emotional statuses. Yet those records don't necessarily belong to the patient. The question this raises in the digital age is: Just how much control should people have over their own records?

Electronic health records (EHRs) have become invaluable collections of information used by a diverse group ranging from government agencies and disease researchers to marketing firms and for-profit data brokers. Government and for-profit businesses have long collected, parsed, and used collective patient data to track the path of chronic conditions and contagious diseases, follow the success rates of new and old treatments, develop new cures, and improve the quality of providers' services. But because today's electronic records are easily shareable -- and hackable -- and have different rules depending on state and organization, some patients fear they have little to no control over the information that tracks their very personal health information.

"It's like we have a vacation home, and we've given out keys to 50 different people, and they all show up at the same time," says Chris Zannetos, CEO and founder of security developer Courion, which counts healthcare organizations as about one-third of its customers. In other words, as patients we want our data to be shared when needed, but then we're surprised at how quickly we lose control of how it's shared.

Consumers don't "own" their health records any more than they own the vast troves of data that retailers, financial institutions, and government agencies collect about them, says Dr. Josh Landy, a physician and co-founder of Figure 1, a text-messaging app for healthcare professionals. Instead of ownership, healthcare professionals and patients should discuss electronic patient data in terms of "stewardship," he says. Although the creator of the record -- such as a hospital or physician's practice -- controls the record and data, patient data has multiple stewards.

Complete records might well include a combination of handwritten medical notes scanned as PDFs into a patient's file; information manually or electronically entered from monitoring and collection tools such as stethoscopes and scales; and data entered directly into the EHR. And the picture is going to get more complex. Soon, electronic records might collect data from wearable devices -- purchased as consumer gadgets -- that gather health data around the clock.

[Why isn't healthcare greener? Read Healthcare IT: Stop Sending PCs To Landfills.]

In addition, consumers often see a variety of healthcare practitioners. Each one -- primary care doctor, orthopedic surgeon, hospital doctor, or psychiatrist -- typically uses the referring doctor's record and creates a copy appended to his own electronic health record for the individual.

With all this sharing, what if a patient has a diagnosis he doesn't agree with or doesn't want shared? Can he contest, say, a diagnosis of alcoholism?

"We have to give due course to the patient," says Richard Rosenhagen, assistant VP for EMR/HIM/CDIP at South Nassau Communities Hospital. "If you're not transparent, you're going to end up in a bad place." The hospital has a process for discussing such conflicts with patients and making their disagreement part of the record, though the diagnosis remains. "If they disagree with what's in there, they have a right to voice their opinion," he says. "That disagreement doesn't give them the right to amend the record."

Incorporating more patient-driven data changes will present a whole new set of challenges for health IT professionals.

One reason is that, as a rule, consumers are "horrible historians," says John Hoffstatter, a physician's assistant and delivery director of advisory services at CTG Health Solutions. People forget to bring in a list of current medications or don't know why they take a particular pill. Having patients read through their electronic record is essential to improve care and reduce costs, he says.

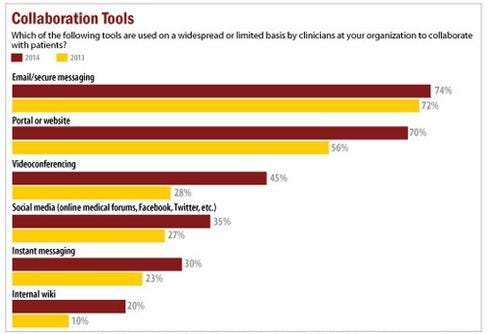

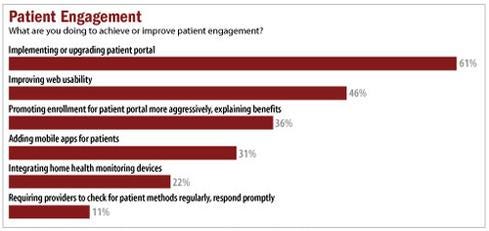

Figure 3:  InformationWeek Healthcare IT Priorities Survey of 322 healthcare technology professionals in February 2014 and 363 in January 2013.

InformationWeek Healthcare IT Priorities Survey of 322 healthcare technology professionals in February 2014 and 363 in January 2013.

Without patient participation, people can, for example, undergo duplicate medical tests when they see different doctors. That could hurt the patient, especially if radiation is involved, and result in extra expenses for payers and for patients responsible for co-payments. But getting patients interacting with their records this way is a big mindset change for doctors and patients.

"Traditionally, when I started practicing way, way back, the healthcare information was really owned by the provider. It was proprietary and part of that was for legal reasons," says Hoffstatter. But the healthcare industry can't ask patients to take a bigger role in their care -- including paying for more of their own treatment -- while also limiting data access. "The problem is we told [patients] for years and years, 'You can't have your information,'" Hoffstatter says. "Now we're saying you should own your information and be [a participant] in patient engagement."

The CIO's role

The CIO is responsible for creating the foundation for a new culture of transparency. Automating routine processes -- such as patching and provisioning of new or expired users -- is critical to giving patients secure access in an environment that frequently changes, Courion's Zannetos says. Usually working in tandem with department heads and healthcare end users, CIOs and their C-level counterparts are charged with implementing systems that encourage consumers to visit and interact with patient portals in order to meet Meaningful Use requirements.

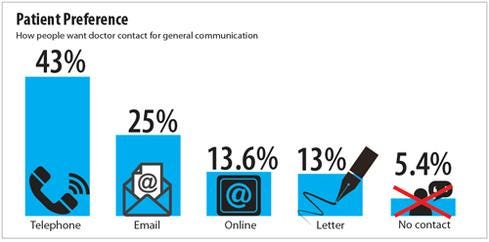

Figure 2:  Technology Advice study, August 2014.

Technology Advice study, August 2014.

Many healthcare providers install patient portals to promote a sense of consumer record ownership or interaction. About half the hospitals in the United States and 40% of physicians had a patient portal, according to Frost & Sullivan's September 2013 study, "U.S. Patient Portal Market for Hospitals and Physicians". Most portals were part of clinicians' practice management or EHR software purchases, the study found. Practices will spend a forecasted $898.4 million on patient portals by 2017, and yet providers often struggle to get consumers to use them. Under Meaningful Use Stage 2, the federal system of incentives and penalties currently in force, providers must ensure 5% of patients use a portal before they attest for compliance. Yet almost two-thirds of organizations report only 0% to 5% of patients are participating, an August report by Peer60 found.

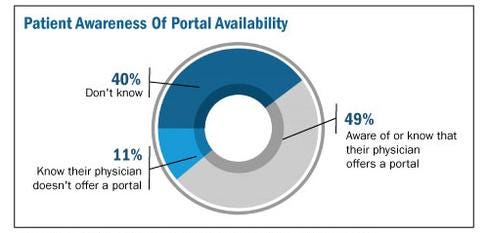

One reason? Patients might not know the portals exist, a recent TechnologyAdvice study on portals revealed. Only 49% of patients knew whether their physician had a portal; 11% knew their doctor did not use a portal; and 40% did not know their physician's portal policy, the study found. Other than billing

or payment notifications, about 48% of primary care doctors did not follow up with patients after a visit and of those who did, only 9% used their portal to do so, TechnologyAdvice found. Instead, they used less cost-effective means, such as phone (24%) or letter (13%).

To encourage portal adoption, CIOs must ensure these systems are easy to use and provide patients with valuable information. Providers typically rely on staff and volunteers to encourage enrollment, often when the patient is admitted to a hospital or during a doctor visit. That's the approach Florida Hospital Celebration Health takes. The hospital is designing a portal where released patients can review their records, watch videos related to their treatment, receive lab information, and stay connected to the hospital.

"We are looking at ways we can leverage technology to keep those patients engaged," says Sandra Reeder, director of nursing at Florida Hospital Celebration Health. "Again, trying to keep them engaged so as soon as they leave so they don't feel everyone's washed their hands of them."

That's also the approach for South Nassau Communities Hospital. The hospital installed FollowMyHealth portals from Allscripts as part of its effort to achieve Meaningful Use Stage 2. Volunteers help patients create accounts while they're at the hospital, and participants receive access to records, lab reports, discharge summaries, and other personal information.

Figure 5:  Technology Advice study of 430 patients who had seen their primary care physician within the last year.

Technology Advice study of 430 patients who had seen their primary care physician within the last year.

Consumers can populate portal profiles with their photographs, demographic and family history information, and other data, and access their file from any computer, says Rosenhagen. The cloud-based portal is always current, and automatically updates whenever patients are seen as an inpatient at the hospital or emergency room, he adds.

"That's giving the patient more information, at no cost to them, and it's what patients have really been crying for a long time," says Rosenhagen. "The bureaucracy, the way it was set up, never allowed the patient to freely access their information. They always had to pay somebody to get somewhere."

Before EHRs, hospitals in New York could charge up to 75 cents per page in copying fees -- for records that could run to several hundred pages. Downloading patient data to CDs, which South Nassau Communities considered, is time-consuming, inefficient, and costly.

"The only way you can succeed is by being transparent," Rosenhagen says. "The more savvy people get, the more demands will be made and the more a hospital has to respond. They have to be totally transparent and absolutely committed to make it right."

Access can, of course, create the occasional problem if a patient disagrees with a diagnosis. In a case like this, Rosenhagen reviews the EHR entries, brings together the different parties, and determines how clinicians made the diagnosis. When facing an unpleasant nomenclature, some patients fight the entry in their record. Providers must review complaints or disagreements, even if ultimately the doctor's diagnosis is determined to be valid. "If we made a mistake we have to fix it, and we have to find out why it happened and how it happened," says Rosenhagen. "We might also find it's not a mistake" but merely a patient who doesn't want something like alcoholism on his or her medical record.

If the diagnosis stands, South Nassau Communities will include the complaint and the patient's response.

"Every time that record is printed or reviewed by anyone, that complaint in the words of the patient and signed by the patient, dated by the patient, will be available for them as well," Rosenhagen says. "People can make an educated understanding of what took place. It's there, but we may not have found the ability to make that addendum or amendment because we couldn't prove it."

The government mandates healthcare organizations allow consumers to review and annotate their EHRs, although providers don't necessarily have to amend their records if they stand by their original prognosis, says Brenda Tso, associate attorney at healthcare specialists Khouri Law Firm. EHRs can, therefore, include doctors' original diagnoses, patients' disagreements, and the providers' ultimate conclusion. Subsequent providers then can review the entire electronic file, she says.

"I think that was the intent of the laws: To give greater access to the patients but also allow hospitals the ability to make a justified attempt to learn the facts," Rosenhagen agrees. If the facts don't justify changing the record, the hospital needs to be able to make that call and justify the reason why, he says.

Limiting access

As stewards of patient data, it's incumbent on healthcare providers to prevent unauthorized people from accessing records. That includes staff members who might want to nose into a neighbor or ex-spouse's condition, even when they are not treating them. South Nassau installed the patient privacy

application FairWarning. The software tracks whether employees or clinicians have legitimate reasons for opening particular records.

Because the software records anyone who accesses a record, "you can't hide from the EHR anymore like you could with a paper chart," Rosenhagen says. He contends the EHR provides a more secure environment than paper records did.

Courion, which developed similar software, has clients such as Miami Children's Hospital, Quest Diagnostics, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. They use its software to automatically update hires and terminations to limit access to authorized personnel retrieving legitimate information, says Courion's Zannetos.

The right to patient records changes over time, creating an added challenge. Parents, for example, control access to children's EHRs -- while they're children.

"Once they turn 18 you've got to turn that off and give access to the 18-year-old, who's supposedly no longer a child," says Zannetos, father of two young adults. Zannetos says the healthcare industry needs to learn from the credit card industry, and how it considers a wide range of factors to spot fraud. "We have to constantly watch through the very complex connections between people, apps, access rights, and what they're doing, and raise alerts when things look like they're out the norm," he says.

IT departments also must guard against patients' errors. All too often consumers use the same password for multiple sites. If a breach occurs at an unrelated site, users might think their data is secure but cyberthieves could now have the password that protects their personal health information, Zannetos says. Organizations might want to enforce frequent password changes, require multicharacter passwords, or assign passwords to consumers, rather than allowing them to use their own creation.

Figure 4:  InformationWeek 2014 Healthcare IT Priorities Survey of 322 healthcare technology professionals, February 2014.

InformationWeek 2014 Healthcare IT Priorities Survey of 322 healthcare technology professionals, February 2014.

Some providers have moved beyond portals and extend complete access to patients through the Open Notes initiative, says David Harlow, principal at The Harlow Group, a healthcare legal and consulting firm. In March, for example, WellSpan Health began offering patients access to office-visit notes, as well as lab results, physicals information, immunizations, and imaging studies.

"It means really sitting side by side with a patient in front of the computer screen, rather than having the computer screen between the doctor and patient, in order to share that information in real-time during the office visit," Harlow says. "It's a real culture change."

To promote access to all electronic records, regardless of providers' EHRs, the federal government and participating partners use Blue Button, a technology that lets consumers click on a blue link to view online, download, and share their records. Although not all providers participate today, HealthIT.gov claims the roster is expanding rapidly.

All for one, one for all

There is a point at which patients lose control of their data; that is when identifiable information is removed and organizations use the vast collection of health data for analytics.

"If it's de-identified, then it's not considered to be that patient's information anymore," Harlow says.

HIPAA recommends one formal process to de-identify data. It requires stripping out all potentially identifiable information, an approach that safeguards patients but deprives researchers, he says. Statistical de-identification, which uses techniques that allow inclusion of certain demographic points, is more valuable to researchers, Harlow adds. Optum Labs, for example, uses multiple de-identification steps when it receives data from Humedica and provides pockets of data to authorized researchers, says Paul Wallace, chief medical officer at Optum Labs. Both approaches satisfy HIPAA rules to preserve patient anonymity, although statistical deidentification -- while more useful -- is also more costly.

Organizations use this statistical de-identified patient data for everything from healthcare and provider quality control and treatment improvement, to researching new medicines and finding new relationships between disease cause and effect.

However, statistically de-identifying data isn't perfect. In a study last year, the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, a nonprofit research and teaching institution with programs in cancer research, developmental biology, genetics, and genomics, was able to re-identify 50 people who had sent personal DNA data in genomics studies such as the 1000 Genomes Report. The odds of being named from a de-identified database were 4 in 10,000, according to a 2005 study. Since that year, consumers share more identifiable information via social media and apps, and more information is digitally available, so perhaps it's more likely to be identified today.

Rather than de-identify data, researchers should be held responsible for protecting personal data and privacy, recommends an article on the Association for Computing Machinery's website written by Jon P. Daries, Justin Reich, Jim Waldo, Elise Young, Jonathan Whittinghill, Daniel Thomas Seaton, Andrew Dean Ho, and Isaac Chuang. Although they focused on students in higher education, the authors argue de-identification forces changes to data that threaten analysis and weaken the results. Too much concern for de-identifying could stifle important research, they say.

Patients worried about their data being re-identified might lie to medical professionals, to hide alcohol, drug, or physical abuse, or conceal embarrassing symptoms. Others are concerned insurers or employers will combine readily available credit card information with health data to paint clear pictures about consumers' cigarette, fast food, or liquor purchases.

Although one person's information speaks solely to that individual's health, the records of an entire population paint a broader picture, one that holds clues to cures, treatments, and prevention. Consumers might generate their personal health data, but they don't own their records. If we're all to reap the benefits of that collective knowledge, it's up to organizations that steward this data to protect it from those that seek to use it for illegal, unethical, or harmful purposes.

Download the entire September issue of InformationWeek Healthcare.

About the Author

You May Also Like