NCA’s Plaggemier on Finding a Path to Data Privacy Compliance

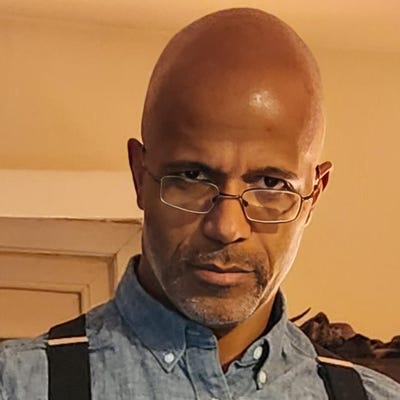

The executive director of the National Cybersecurity Alliance says organizations often look to the toughest data privacy laws to sort out compliance strategies.

.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=95&format=jpg&disable=upscale)

Companies concerned about data collection practices and usage, compliance, and escalating privacy regulations may want to look to a warning from a now classic piece of science fiction.

Perhaps accidentally, insight from Lisa Plaggemier, executive director of the National Cybersecurity Alliance, echoes the original “Jurassic Park” movie’s ethical concerns about technology and commercialization getting ahead of themselves -- unlike Ian Malcolm, her focus is on how data gets handled rather than dinosaurs.

“Just because you can doesn’t mean you should,” she says. “Just because the data is available, just because there’s no specific regulation prohibiting you from doing a certain something, it doesn’t mean it’s the right thing for you to do as an organization.”

The attention data privacy gets these days is often in response to regulations and enforcement being dished out or is on the way. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) went into effect in 2018 and domestic US policy is trying to catch up, though state-level legislation such as the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) have emerged in the absence of national regulation.

Last year, Meta and TikTok got hit with significant GDPR fines, putting other companies on notice. Meta’s $1.3 billion fine focused on personal data being transferred from Europe to the United States and suspected surveillance practices in the US. Meanwhile, TikTok was fined $370 million for how it processed personal data of children -- whose accounts at one time defaulted to public status. TikTok pushed back that it made changes with parental controls and default settings prior to the fine being issued.

Domestic US enforcement of privacy law has also led to notable fines. Last September, Google agreed to a $93 million settlement with California in response to alleged location-privacy violations under the state’s consumer protection laws. In 2022, Sephora agreed to pay a $1.2 million settlement with California over allegations the retailer sold consumers’ personal information without informing them -- while its website stated it did not sell such information.

Plaggemier says states have shown a readiness to deliver on enforcement, even though national legislation in the US has yet to be ratified. “They’re no longer sort of waiting on the federal government to take action,” she says. As organizations see different states pass different legislation, Plaggemier says companies tend to adhere to the strictest, most stringent laws as the default to keep compliance manageable.

“Right now, you’ll hear a lot of companies saying that they’re complying with CCPA across the board because it’s too hard to figure out when what regulation applies to which customers,” she says. “If we continue going down this road, where different states take action to different degrees, what’s going to happen in the everyday world, the business world, the most stringent regulation is going to win and that’s what everybody’s going to chain themselves to.”

With the rapid-fire evolution of technology, Plaggemier says, federal legislators have yet to keep pace. This has led to a patchwork of policy in the US -- for some states, data privacy is not a priority, which can leave it up to organizations to make their own decisions, ethics considerations, and brand identity about data privacy, she says. “It really becomes a question of who are you as an organization? What are you about? What do you think is the right thing to do?”

There has been a common theme, Plaggemier says, in her recent conversations with chief privacy officers where their jobs were becoming more akin to advisory roles where they discuss overall policy within their organizations -- where it may feel like a bit of a free-for-all with such piecemeal US regulation. “It kind of falls back to the organization to decide at their core who they are,” she says. “Do they want to be the type of organization that does things that maybe consumers aren’t really crazy about? What do they stand for? What are their own practices? What are their own policies?”

On the international stage, companies are becoming more aware of the more active and robust policies they may face and the penalties they can carry. That has led to some patterns, Plaggemier says, developing around what is reasonable for companies to enact in relation to their sector and industry. “Do you have security or privacy tools or practices in place that are in line with your competitors?” she asks. While such an approach might be considered reasonable at first, competitors might be way ahead with much more mature programs, Plaggemier says, possibly making copying rivals no longer a reasonable approach and compelling companies to find other ways to achieve compliance.

Data privacy regulations continue to gain momentum, and she believes it will be interesting to see what further kind of enforcement actions develop and how the courts in California, for example, manage. As CCPA and other state-level regulations continue into their sophomore eras, Plaggemier says at least a few more states seem likely to get on the bandwagon of data privacy regulation. Meanwhile, there is also some growing concern about how AI may play a role in potential abuses of data in the future.

“The threat of AI is feeling close to existential at this point just because of how much smarter and more efficient it’s going to make the cyber criminals and the nation-state actors,” she says. “We’re already seeing that and coming into an election year. That keeps me up at night.”

Read more about:

RegulationAbout the Author

You May Also Like