Is 1% Improvement Boring, Or A Breakthrough?

To tap the Internet of Things, CIOs need to bridge the gap between the culture of grinding out small wins and the Silicon Valley disrupt-or-nothing mindset.

Here's how two business cultures react to a 1% improvement in a company's operational efficiency:

General Electric: Holy crap!

Silicon Valley: Yawn...

How do you feel about a 1% improvement in your business? I got to thinking about this idea of incremental improvement as I listened this week to GE CEO Jeffrey Immelt trumpet the potential of the Internet of Things, what GE calls the Industrial Internet.

The Internet of Things requires companies to put sensors on the right devices, machines, and other "things," analyze the data that comes in, and change a process to become more efficient or to offer a new and better end-product. To get there, and generate commensurately higher revenues and profits, companies will have to combine emerging tech with established processes and products.

CIOs are in the right spot to lead their companies onto this cultural tightrope walk, to mix the tactics of the 1% grinders with the Silicon Valley disruptors.

But make no mistake, we're talking vastly different cultures here.

Silicon Valley thrives on disruptive change. Incremental improvements are the devil, tempting you to settle for small ideas. The blind spot, though, is a sense that there's not much to learn from even huge companies in places like Omaha, Houston, Charlotte, and Detroit.

Immelt -- speaking at this week's user conference for GE Intelligent Platforms, GE's growing software business -- alluded to this cultural gap when he said, "Sometimes in Silicon Valley there's a notion among software companies that machines don't matter. In the world we live in, in the industrial world, machines count."

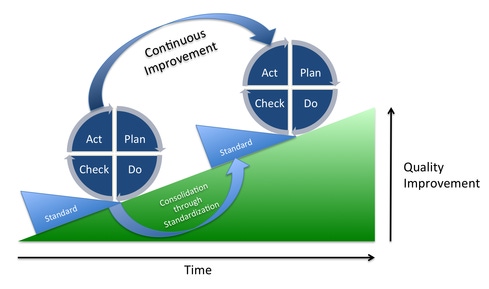

On the other side, the culture that respects those 1% gains, established companies know the profitable power of grinding out small wins, year after year, and applying them at massive scale. That's what GE is selling with its 1% story, like saying that if data analytics could drive a 1% improvement in fuel consumption on all GE jet engines it would bring $3 billion in added profit for airlines. "Small changes in the industrial setting, given the value of the equipment and the assets, are worth tens of billions of dollars," Immelt said.

Providing a real-world example, Jeff Slagle, GM of propulsion engineering at Delta Air Lines, described how Delta analyzes jet engine performance daily, using performance data collected from sensors on the engines. He pointed to a small spike on a graph that showed one engine that wasn't at peak efficiency, and thus would burn more fuel -- about $14,000 worth a month, for just one of the 1,400 engines Delta runs every day.

But industrial companies know that 1% can cut both ways, that tech-driven change gone badly at scale also can burn up billions of dollars -- by shutting down a factory, refinery, or freight train, or running them afoul of regulators. So the bias among these 1 percenters is toward slow and safe. Their blind spot is that large-scale, software-driven innovation can wait until tomorrow, when someone else has worked out the bugs.

GE is trying to bridge this gap between the industrial grinders and the Silicon Valley disruptors by setting up a major software development center in San Ramon, Calif. Rich Carpenter, CTO of the GE Intelligent Platform software group, says the company wouldn't have tackled Hadoop for big data analysis of industrial systems without a push from its Silicon Valley culture. Sure, GE had data scientists before opening the San Ramon center, "but they were squirreled away in the labs," Carpenter says. "They weren't mainstream. They weren't the cool job they are today."

But companies don’t have to set up a Silicon Valley office to bring together the disruptors and the grinders. Innovation labs, hackathons, data science teams, Agile development teams, embedded IT specialists -- CIOs can use all of these approaches to make their IT organizations more responsive and open-minded to business needs and the possibilities of new technology.

Immelt argued that every industrial company must become a software and analytics company to compete. "The product, the machine, is kind of table stakes. It's the foundation. But those machines are now surrounded by analytics," he said.

Getting there will require companies to embrace the disruptive thinking Silicon Valley thrives on, but without becoming a snob about those hard-fought 1% gains that pay the bills.

While there's a role for PhD-level data scientists, the real power is in making advanced analysis work for mainstream -- often Excel-wielding -- business users. Here's how. Get the Analytics For All issue of InformationWeek Tech Digest today. (Free registration required.)

About the Author

You May Also Like