Phoning Home From Mars On Christmas Eve

For six simulated space explorers, practicing for a Mars mission means never having a real-time conversation with anyone "back on Earth."

8 Quiet Firsts In Tech In 2014

8 Quiet Firsts In Tech In 2014 (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

On Christmas Eve, my phone chirped, and I saw it was a message from Mars.

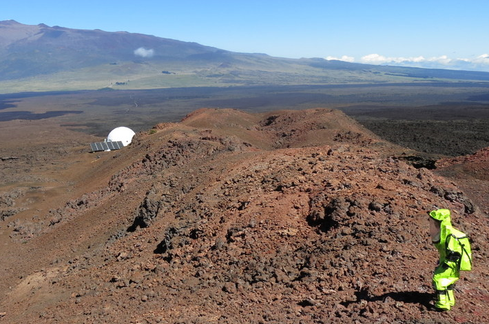

All right, not Mars exactly, but a message from a crew of three men and three women in the midst of an eight-month stay in a simulated Mars habitat on the slopes of the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii. The mission, which began in October, will be the longest Mars simulation conducted by the U.S. (the Russians have done longer ones). More than anything else, the goal is to study the social dynamics of what it would be like to live in a pressurized dome, isolated from the rest of society, and cooped up in tight quarters with five other people -- unable to go outside except in the confines of a "spacesuit."

Figure 1:  The HI-SEAS crew on Christmas.

The HI-SEAS crew on Christmas.

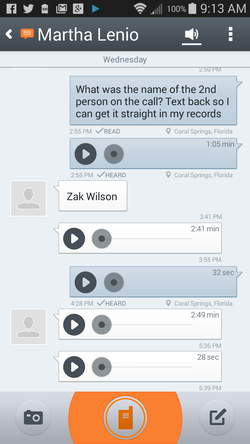

One piece of that experiment is an Android app on my phone that simulates the asynchronous pace of voice communications over distances where the speed of light imposes a delay on every transmission, making normal conversation impossible. Every voice transmission, text, and email is queued and held for 20 minutes prior to delivery to approximate the one-way transmission lag for a signal to pass between Earth and Mars (the actual delay varies based on the relative positions of the planets). The delay means that any back-and-forth exchange takes at least 40 minutes.

I pressed play and heard from Martha Lenio, mission commander of the Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS) Project run by NASA and the University of Hawaii. She was getting back to me a few hours after I messaged her (working around earthly time zones, as well). First question: How realistic is this simulation of living on Mars?

"I think it's fairly realistic for voice messaging because of the delay," she said.

Figure 2:  Exchanging Voxer messages with Martha Lenio.

Exchanging Voxer messages with Martha Lenio.

Yet the experience also suggests that voice will not be the most appropriate mode for a lot of communications with ground control. "The voice part is good for talking to family and friends but not so good for talking to mission support people -- just because we want to have a written record of it," said Zak Wilson, another crew member joining in the call. Lenio agreed that email was often better, because it was searchable and easy to scan quickly.

There are exceptions. While working on some technical troubleshooting tasks, Wilson said, he found himself talking through his questions for the support team, because it was faster than typing or texting them.

For voice communications, HI-SEAS worked with Voxer, which makes an app that functions in walkie-talkie mode for communication between members of a team but switches to asynchronous messaging mode if the other person is not online to take the call. The same app supports texting, so you can have a threaded conversation that mixes voice and text messages. The enterprise version of the Voxer app works with an intranet server, and prime customers are government agencies that want to maintain private communication channels. NASA customized the server to work with the delayed voice loop. It was Voxer that reached out to me, wanting to talk about its role in allowing the HI-SEAS participants to talk with their families at Christmas.

I wrote a very similar story a couple of years ago about NASA's simulation of the communication and training challenges of an asteroid mission through NEEMO, an underwater space simulation environment off Key Largo, Fla. Voxer participated in the most recent NEEMO exercise, as well, according to president Irv Remedios. Under Earth conditions, Voxer's asynchronous messaging is about allowing messages to go through even

on intermittent or unreliable connections, he said, but here the key thing is that "we're integrated at the network layer" into the simulations.

Aside from practicality, "it's really nice to hear people's voices," Lenio said. "The other day, a friend called, and she was so emotional -- it's really nice to be able to get that across."

"I use it more as an alternative to text and SMS -- and I tend to do more texting -- but it is nice to hear my mom's voice and my friends' voices," Wilson said.

According to Lenio, having voice communications arrive as voicemail also tends to be better for scheduling so that tasks not be interrupted. She didn't reply to my first message right away, because she received it at about 7:00 a.m. Hawaii time, and in the cramped crew quarters it would have been rude to talk into her phone when others weren't yet awake. Then she went out on extravehicular activity (EVA) before calling me back.

Once started, our conversation proceeded as a staggered stream of one-way messages (with a certain amount of "Um, yeah" verbal clutter thrown in to make up for the lack of an immediate response).

I asked if they were getting a sense of how lonely a Mars mission would be. John Young, the astronaut whose career stretched from Gemini to the Space Shuttle, with two Apollo missions in between, once said that travel to Mars would be a whole different kind of lonely. I'm paraphrasing from memory; he spoke to a Society of Professional Journalists event I attended more than 20 years ago, but the phrase stuck with me. Young had experienced the loneliness of manning an Apollo command module, stuck in orbit while two colleagues explored the surface of the noon. (He later got his chance as a Lunar Excursion Module pilot.)

If it's realistic to suppose an expedition to Mars would consist of something like six people on the surface, the HI-SEAS crew doesn't see loneliness as the biggest challenge.

"This is probably the most intense social thing I've ever done," Wilson said. "We're around each other 24/7. We have a tiny little bedroom and don't spend much time in that. I probably have more interaction here with people in a day than I did in a week in my cubicle job.

"We're not lonely; we're isolated," he said. "Those are two fairly different things in this circumstance."

"It's a little like being on a camping trip," Lenio said. "We're isolated from society, I guess, and it's hard communicating. But at the same time, you're with people all the time, and you're never alone."

Figure 3:  EVA with the dome habitat in the background.

EVA with the dome habitat in the background.

(Image: Zak Wilson's Almost Mars blog)

Wilson said the harder part is being isolated from nature. "Only being able to go outside in a hazmat suit is tough. There's no wind on your face, no fresh air -- it's not the same at all." (He has also blogged about that aspect of the experience).

Though Voxer and email work pretty well through the communications loop, Lenio said, accessing the limited set of whitelisted Internet applications available to the crew can be awkward. Sometimes it simply doesn't work; communications are garbled by the message-delay software.

The mission also has to operate on a limited supply of solar power, and on occasion an overcast day will make that difficult, she said. Even on a normal day, it's important to finish cooking supper before the sun goes down, or there may not be enough power for the stove.

The highly scripted nature of a NASA mission, real or simulated, can be an irritant. The HI-SEAS crew complaints are not so different from the picture of life in orbit aboard the International Space Station as described in Charles Fishman's article in the current issue of The Atlantic Monthly.

"Unless something breaks down, we pretty much know what we're going to be doing for the day," Lenio said.

"Yeah, we don't have too many good surprises here," Wilson said. Most of the time, boredom is the bigger enemy.

That makes it all the more important that team members tend to get along with each other. "We're in really good company here, so we don't feel that isolated," Lenio said. "I think they did a really good job picking the crew."

Apply now for the 2015 InformationWeek Elite 100, which recognizes the most innovative users of technology to advance a company's business goals. Winners will be recognized at the InformationWeek Conference, April 27-28, 2015, at the Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas. Application period ends Jan. 16, 2015.

About the Author

You May Also Like