Do Clickers Beat PCs For Testing Students?

Handheld devices typically used for informal polling and quizzes get attention as an alternative for digital testing, following online testing failures in several states.

10 Tech Tools To Engage Students

10 Tech Tools To Engage Students(click image for larger view)

Could the humble clicker be a simpler and more reliable way of digitizing testing in schools across America?

Turning Technologies sees an opportunity to promote a variation on the handheld devices typically used to informally poll groups of people: as a cheaper and more reliable alternative to computer-based testing, which recently has hit some rough spots in the states that have been the most aggressive about implementing it.

Turning's Triton Data Collection System allows a handheld clicker to be used in place of the color-in-the-bubble paper tests that generations of students became familiar with as a way of completing tests. The questions can still be delivered on paper, and students answer at their own pace, using the clicker's simple keypad. It's a slightly more advanced take on the clicker's use as a way for instructors to get quick feedback on questions posed to the class.

The clicker is "an older technology, but it's absolutely dead-on reliable," Tina Rooks, Turning's senior VP and chief instruction officer said in an interview.

[ Here's another take on digital testing: iPad Exam App Takes Testing Offline. ]

Reliability has not been a hallmark of automated testing that relies on PCs connecting to servers over the Internet, as Indiana, Kentucky, Minnesota and Oklahoma found out this year. "Thousands of students experienced slow loading times of test questions, students were closed out of testing in mid-answer, and some were unable to log in to the tests," EducationWeek reported. "Hundreds, if not thousands, of tests may be invalidated. The difficulties prompted all three states' education departments to extend testing windows, made some state lawmakers and policymakers reconsider the idea of online testing, and sent district officials into a tailspin."

The issues were particularly pronounced in Indiana, where testing was interrupted for an estimated 80,000 Indiana students; an additional 67,000 also were said to have encountered some disruption in the process of taking the state's standardized assessment.

"We use technology a lot, so we recognize there are going to be glitches. But this was not just a glitch -- it was a complete breakdown," said Krista Stockman, public information officer for the Ft. Wayne Community Schools.

The source of the problems in Indiana was apparently server overload. When the assessment provider, CBT/McGraw-Hill, was called on the carpet at a State Senate hearing, an apologetic company president Ellen Haley explained that the load testing and simulations conducted in advance apparently underestimated the demand that occurred in practice.

Online delivery of standardized tests is being promoted as the wave of the future, partly thanks to the rise of the Common Core State Standards initiative and the assessment design work of a couple of state consortiums, the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium and the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC). The U.S. Department of Education is also supporting the modernization of test technology.

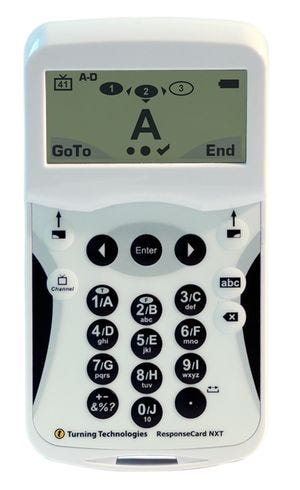

Turning Technologies clicker

Turning Technologies clicker.

Yet there are ways of digitizing assessments without making every student's performance dependent on the performance of the network or of a remote server.

The Triton system is designed to be fail-safe and able to work in "low to no bandwidth" settings. Rather than downloading a question at a time from a remote server and posting the response, questions are delivered on paper and stored in a "triple redundant" scheme -- meaning encrypted answers are stored on the device, on a "receiver" (a classroom PC that caches the data) and on a centralized server. But if the connection to the server is interrupted, or the receiver PC fails, the answers can be relayed up the chain later. On the other hand, when everything is working right, test results are ready for analysis just as quickly as they would be if students took their tests on PCs.

Rooks argued that's a better design for high-stakes assessments. "At the moment of testing, it can't fail," so simplicity and redundancy are important, she said. The clicker solution could also be a lifeline for cash-strapped school systems wondering where the money is going to come from for all the computers and network upgrades required for online testing. With the clickers, one computer in a room can support the testing of up to 500 students, she said.

Bruce Umpstead, director of Michigan's Office of Education Technology & Data Coordination, sees potential for the technology, at least as a transitional measure. "If there was a way to use Triton in Indiana, they might not have had as many problems," he said.

Under a grant Umpstead administered, Michigan did a pilot test using an earlier prototype of Turning's assessment system for the "quasi-high-stakes" ACT Explorer test, which is a middle school or early high school test of academic readiness. After having almost 10,000 out of 100,000 test takers use the devices successfully, it's easy to see the solution scaling quickly to "be used as an interim step toward a full online solution," he said.

"This could be less expensive and I believe, in the interim, more safe and reliable" than going to computer-based testing prematurely, Umpstead said. "The schools seem to love it." Umpstead said it's not his role to recommend technology options, but he does oversee programs to help school systems prepare for the network and system demands of online testing. Although Michigan schools are already close to meeting the minimum technical criteria laid down by the testing consortiums, one of his concerns is to plan for excess capacity to minimize the likelihood of the kind of system overloads that occurred in Indiana. Policy makers in his state and others eventually want to deliver standardized tests online, so before Turning could play a role in high-stakes testing it would have to be approved by them as an alternative, he said. Test publishers would also have to support the use of the device.

Meanwhile, Umpstead said he would be interested in promoting further evaluation of the usefulness of the devices but does not currently have funding to do so.

Wendy Zdeb-Roper, executive director of the Michigan Association of Secondary School Principals, said the members of her association are also interested, partly because "there's a lot of concern about schools not being ready with their bandwidth" for online testing.

Both Umpstead and Zbeb-Roper said their interest was not only in high-stakes testing but the potential for the devices to be used in more routine assessments, such as the quiz a teacher might administer at the end of a day's lesson. "There are both short-term and long-term possibilities here," Zbeb-Roper said, meaning the clickers could be both a "stopgap" solution on the way to online testing and a tool for "daily formative, common assessments."

Richard Mayberry, a former teacher who now works as a technology coach for the Lapeer, Mich., schools said it strikes him as unrealistic to expect that schools will be able to provide all the computers and all the bandwidth for fully online testing. In the pilot project he participated in with the Turning clickers, there was one small glitch where a student's data wasn't transmitted correctly, but it was still stored on the device and available for upload. "It's got that redundancy in it, and that's comforting," Mayberry said.

From the student's perspective, the experience was "pretty much the same" as a traditional bubble test, although some rated it an improvement, Mayberry said. "It certainly wasn't any worse than paper and pencil," he said, and for the test administrators it was better because they got the answers immediately.

Rooks acknowledged Turning must fight the perception that clickers are boring, old technology, soon to be made obsolete by the bring-your-own-device trend in mobile technology. Yet students who have phone batteries die or their mobile Internet connections fade halfway through a test might want to learn to have a little more respect for the lowly clicker, which can be delivered fully charged and need only enough wireless bandwidth to connect to a computer on the other side of the room.

When it comes to test technology, boring is good. The kind of excitement they had in Indiana is just what you don't want.

Follow David F. Carr at @davidfcarr or Google+, along with @IWKEducation.

About the Author

You May Also Like